t was a nice morning on the Big Island of Hawaii as Kevin and Pamela Spitze drove to an art show in Hilo when the words popped up on Kevin’s cellphone screen:

“BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER.”

Then it added for emphasis:

“THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

The Spitzes, who recently moved from Los Angeles to Hawaii’s Big Island, said they were in paradise but already had been living on edge given the recent inflammatory bluster between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un over nuclear annihilation.

“We have such a barrage of negative stuff that has been happening that our senses have been heightened,” said Pamela Spitze, 64. “We thought it was the real thing. We are very concerned.”

For nearly 40 nail-biting minutes, so were millions of other Hawaiians and vacationers. Video emerged of adults removing manhole covers and lowering children into sewers in a desperate attempt to escape a ballistic missile hurtling their way. People broke into tears, told relatives they loved them and scattered back to their homes and hotels, unsure what to do next.

Finally, at 8:48 a.m., 38 minutes after the alerts went out, authorities announced it was a false alarm, a mistake, simply human error.

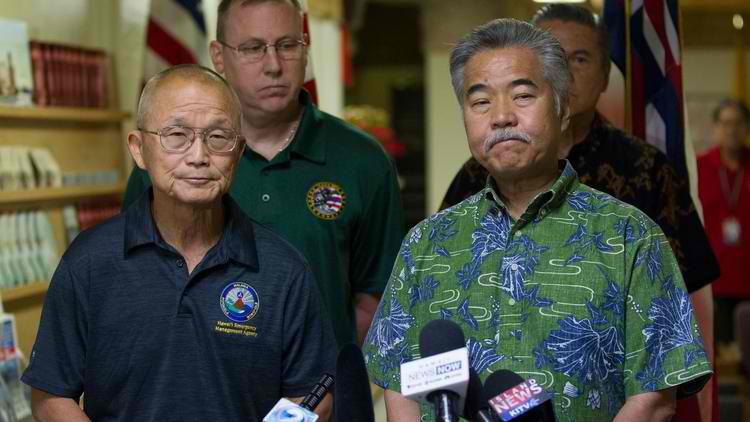

Gov. David Ige called the entire episode “a nightmare,” and officials said they would suspend the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s internal testing system until new protocols are in place to prevent it from happening again.

“Today is a day most of us will never forget,” Ige said in a statement. “A terrifying day when our worst nightmares appeared to become a reality. A day where we frantically grabbed what we could, tried to figure out how and where to shelter and protect ourselves … said our ‘I love yous,’ and prayed for peace.”

Until the all-clear was given, people desperately tried to get information and swamped the 911 system.

“The bad thing is we tried to call 911 and we were really frustrated that nobody picked up the phone,” said Pamela Spitze, a retired community college training program staffer. “It took about 40 minutes before we were told it was a mistake.”

“It took so long for this mistake to be acknowledged,” said her husband, Kevin Spitze, 71, who retired from his job in information technology. “When a mistake like this happens it’s important for the authorities to say quickly this is a mistake.”

At a drugstore in Honolulu, “some people cleared out of the store” when the alert came in, said Gardenia Unutoa, 25, a pharmacy technician. “We all freaked out, me and the daytime pharmacist,” she added. “We were trying to get ahold of our store manager. Then we finally found out it was a mistake. We tried to stay calm, but we were scared.”

According to the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, the false alarm happened when an employee, whom it would not identify, hit the wrong button during routine tests.

Richard Rapoza, spokesman for the emergency management agency, said the worker who sent out the erroneous alarm “didn’t realize his error until he received the alert on his own cell phone.”

The system does ask whether a staffer wishes to send an actual alert, at which point he or she answers yes or no. On Saturday the employee then made a second mistake by clicking yes.

Rapoza said that from now on two employees will be required to send out alerts: one to request the alert and another to verify and send it. He said they had required only one individual to make the process quicker.

“Redundancy didn’t seem important at the time,” he said.

With two people, the process will be a bit slower but not by much. “It may add a few seconds to the alert,” he said.

In an interview, Rapoza also said it took 38 minutes to cancel the alert because a process had not yet been created to cancel false alarms and the agency had to seek authorization from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to send out the all-clear and to use the civil alert system to send out the message that there had been a false alarm.

Vern Miyagi, administrator of the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, said the employee who sent out the alarm “feels terrible.” He labeled it a personnel matter and would not say what action, if any, would be taken.

Ige apologized to island residents and tourists for the panic the mistake caused.

“I know firsthand how today’s false notification affected all of us here in Hawaii, and I am sorry for the pain and confusion it caused. I, too, am extremely upset about this and am doing everything I can to immediately improve our emergency management systems, procedures and staffing,” he said.

Because of growing tensions between the U.S. and North Korea, Hawaii has been preparing for the possibility of a nuclear attack, and TV commercials warn residents to “get inside, stay inside” in the event of any attack. A nuclear warning siren, a holdover from the Cold War blared in December, the first such test in more than three decades.

The governor said Saturday’s scare should prompt some reflection on relations between Pyongyang and Washington. “I encourage all of us to take stock, determine what we all can do better to be prepared in the future — as a state, county and in our own households. We must also do what we can to demand peace and a deescalation with North Korea, so that warnings and sirens can become a thing of the past,” he said.

White House Deputy Press Secretary Lindsay Walters said in a statement that President Trump was told about the false alarm at his Mar-a-Lago property in Florida, where he was spending the weekend.

“The president has been briefed on the state of Hawaii’s emergency management exercise. This was purely a state exercise,” Walters said.

The alert was sent to every island in the Hawaiian chain and every cellphone in the state of 1.4 million people, emergency management officials said.

Among them were Bill and Susan Hulse, who were sitting on the lanai, or porch, of their vacation home on the northwestern coast of Hawaii’s Big Island on Saturday morning. They were drinking locally grown Kona coffee when the alerts flashed on their phones.

Retirees who live in Idaho Falls, the couple bought the condo last year, and planned to spend a week or two each year on the island.

“We thought our biggest risks were tsunamis or volcanoes,” Bill Hulse, 61, a retired engineer, later said while waiting to take a whale-watching excursion. “From the mainland we had heard that Hawaii tested the systems multiple times.”

Some on the islands thought they heard sirens, while others did not.

“I thought it was real,” said Susan Hulse, 57, a retired nonprofit fundraiser. “He didn’t,” she said of her husband.

Bill Hulse added: “If there’s really an inbound missile the military would know instantly, and I’m sure they would interrupt CNN and Fox News.”

The couple said there was nothing on television, so Bill thought it was a hoax.

The Spitzes, like other rattled Hawaii residents, questioned how the false alarm could have happened and why it took so long to get the word out if it was a mistake.

The alert had been made even scarier with the words: “THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

“It takes a long time to calm down from something like that,” Pamela Spitze said. “You go into panic mode.”