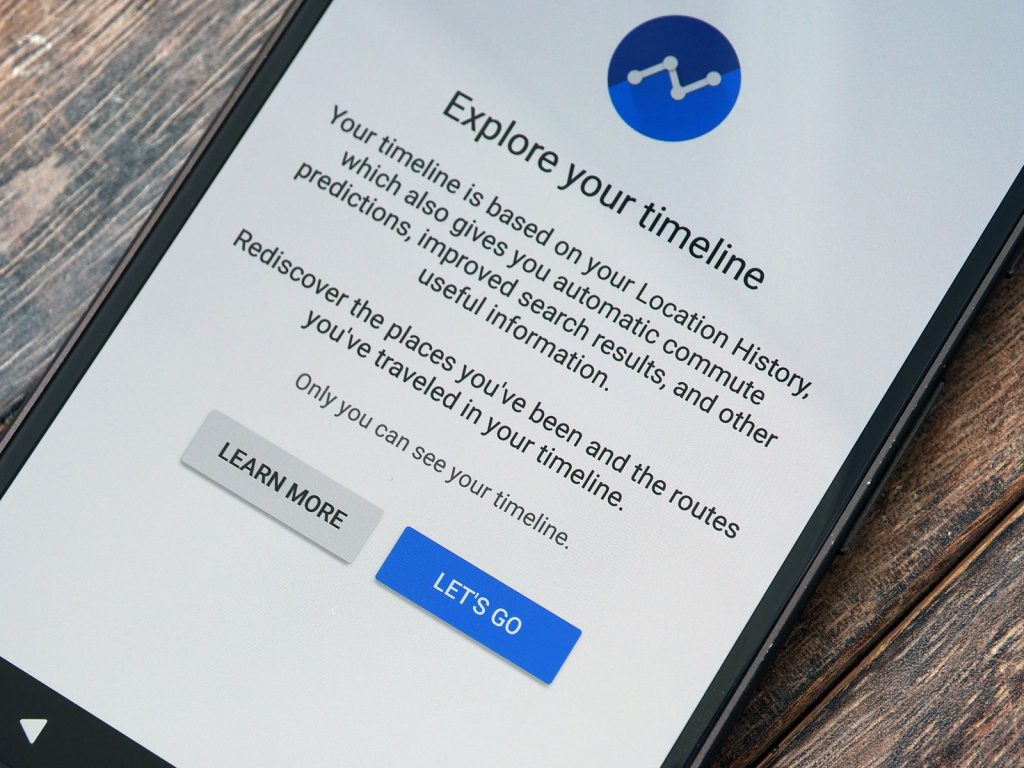

If you’re one of the millions of people with a Google account, you have a Google Maps Timeline. It might be blank — it’s tied to the Location History setting that caused more confusion than needed because of its name, and it checks in periodically on every mobile device tied to your account once you’ve agreed and opted in. For some people, this is helpful for things like calculating mileage, for others, it may be a cool thing to see where you’ve been. For law enforcement, though, it’s become a way to cast a very wide net when looking to see just who might have been around during a crime according to an eye-opening piece by the New York Times.

It’s not a foolproof way to catch the bad guys and a lot of the details about how officials can use the information is a bit cryptic. But a recent case in Phoenix sheds a little light on how the service is being used, or abused, depending on your point of view.

Google, like every company in the U.S., has to provide any information that is accompanied by a lawful subpoena. The company has a fairly good history of fighting these subpoenas, but in the end, a lot of data gets handed over when requested. Google’s database of where you’ve been, internally known as Sensorvault, helps the company show you location based interests and ads. A new breed of warrant, which the NYT aptly calls geofence warrants, taps into the Sensovault database in a way that would make the framers of the fourth amendment shiver.

Law enforcement can take the location and time of a crime and have Google tell them who was in the area. Google has a novel way to attempt to anonymize the data — the company provides a set of tokens that portray an account that police can track and then ask for more precise and identifying data for the ones that fit the scope of an investigation based on other evidence, such as video or eye-witnesses. The case profiled by the Times shows how this can backfire — a man who lent his car to a person who committed a crime and was unlucky enough to be in the vicinity when it was committed was arrested and spent a week in jail as a suspect in a murder case.

Investigators also had other circumstantial evidence, including security video of someone firing a gun from a white Honda Civic, the same model that Mr. Molina owned, though they could not see the license plate or attacker.

But after he spent nearly a week in jail, the case against Mr. Molina fell apart as investigators learned new information and released him. Last month, the police arrested another man: his mother’s ex-boyfriend, who had sometimes used Mr. Molina’s car.

We’re not against law enforcement using every tool at their disposal to try and catch a criminal. We’re also not against anyone who wants to use a service that keeps a timeline of all the places they have been for whatever reason. We do think it’s important that everyone knows how the data collected about us all is used.