Think only young people need to establish great credit scores? That’s understandable. Credit cards are marketed to college students looking to work toward financial adulthood. The thinking is that folks in their early 20s can prove their ability to handle credit responsibly, and sail on from there.

But retired people also need to make sure their credit scores are rock solid, and to try improving them if not. Banks, credit unions, and other lenders base the interest rates they offer, as well as fees, on an applicant’s credit score. It’s not just interest rates, either — getting any credit may be hard if your score is lackluster.

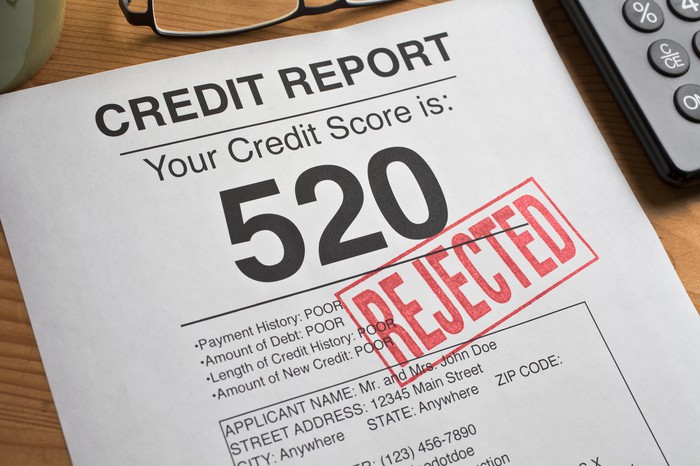

What’s a good score? Lenders usually use a score from a company called Fair Isaac (FICO), though there are many sources. FICO looks at your credit history, crunches the data, and assigns you a credit score of between 300 and 850. A score of 800 or above means your credit is excellent. A score from 740 to 799 is very good. A score between 670 and 739 is good. A score between 580 and 669 is fair. A score of less than 580 is poor.

The U.S. average is 701, according to Experian. But many Americans — of all ages — have much lower scores.

Curious about how you stack up? Credit reports are compiled by the three credit bureaus: Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. All Americans can obtain one free credit report per year. If you want more than one, you’ll be charged.

We’ll give you the lowdown on how the scores are crafted, but first, let’s look at how having a lower score can hurt you financially. If you have an average or lower score, lenders may charge you higher interest rates and fees. The higher the interest rates and fees, the higher your monthly payment will be. High monthly payments may make it difficult or even impossible to live on a fixed income. Plus, your total debt will take longer to pay off with a higher interest rate.

Retirees need good credit for the following three reasons.

1. Optimizing mortgage payments

Back in the day, the standard picture of retirement assumed a predictable life trajectory: Young people bought a house in their 30s, paid a mortgage with a 30-year term, and could retire with the house paid in full.

Increasingly, though, older people are still stuck paying a mortgage. Roughly 30% of senior citizens pay a mortgage bill every month.

That figure is likely to rise in the future, because millennials are forming households at a later age than previous generations did. If you don’t buy a house until you’re 42 and you have a 30-year mortgage, you don’t finish paying off the house until you’re 72. But what if you want to retire at 66?

Most retired people live on a fixed income. A mortgage payment can take up a chunk of it that may make it hard to live comfortably on what you’ve got left over.

Now, mortgage payments can be shrunk if you can refinance to a lower interest rate. But if older people don’t have good credit scores, they may find it difficult to obtain lower interest rates. Lenders may refuse to refinance at all for older people with iffy credit scores.

2. Reducing credit card debt

Older Americans are carrying startlingly high balances of credit card debt. Baby boomers have an average of $7,550, much higher than the $6,354 average across all age groups. Generation X, the generation to enter retirement after boomers, has the biggest average, at $7,750.

Credit card debt interest rates are currently very high. At nearly 18%, they are much steeper than average mortgage rates, which hover around 4%. The high interest rates may make it very tough to pay down credit card debt at a reasonable pace, and thus the cycle of debt begins.

There are several strategies to make credit card debt payments smaller, which can provide relief from a tightly stretched budget, allow the faster repayment of debt, or both. One way is to consolidate credit card debt into a personal loan, which can have an interest rate as low as 10%. Another is rolling over credit card debt into a low or 0% annual percentage rate (APR) credit card. This will reduce or eliminate interest, which can make payments very low.

Unfortunately, both these avenues may be closed to people with average or poor credit, since personal-loan lenders and credit card companies prefer lending to folks with good credit.

3. Obtaining a business loan

Many older people want to develop a business once they’re retired. It could be a long-standing dream previously put on hold while working full time or a way to earn some needed money. It’s a way to be engaged in a new project in retirement and keep some income coming in.

But guess what: Small businesses often require business loans. You may need seed money for equipment or a loan to expand once your business takes off. The terms you’re offered will be less advantageous or you might get outright denied credit if your credit score isn’t good.

The lowdown: Credit scores up close

FICO calculates credit scores by assessing data from five categories. It closely guards the specific formula, but we know the categories and their relative importance.

1. Payment history contributes 35% to your score. The biggest chunk of your score is based on data about whether you pay your bills on time. Paying bills late, having delinquent debt or derogatory marks will hurt your score.

2. The second-largest category is amount owed, which makes up 30%. Amount owed includes (1) how much debt you are carrying, by dollar amount, (2) weight vis-a-vis your available credit, and (3) your current balances versus what you owed initially. In other words, let’s say you currently owe $5,000 on a credit card with a $10,000 limit, and you originally owed $8,000. Amount owed accounts for all of that, looking at this by account and by the aggregate of debt you owe. In general, lenders don’t like to see maxed-out cards or high aggregates, because people who max out cards can struggle to pay their debt service.

3. The third-largest category is length of credit history, at 15%. The longer you’ve proved you can responsibly handle credit, the higher the score in this section will be. FICO looks at the age of the credit card you’ve held the longest, plus the average of all cards, as well as at the individual accounts.

4. New credit is worth 10% of your score. The number of credit inquiries on your record counts in this category. The more hard inquiries (which imply attempts to open new credit or get a loan) over the past year the lower your score in this area may be. The number of new accounts opened also counts. Generally speaking, lenders view many credit inquiries and new accounts as a sign that you need money, which could make them nervous you won’t be able to pay the bills.

5. Your mix of credit also is 10% of the score. FICO looks at how many different types of accounts you have: mortgage, credit card, car loan, and student loans. They believe that the more types of accounts you’ve shown yourself responsible with, the better a credit risk you are.

Once you know your score, make plans to raise it if you need to. Pay your bills on time. Pay down debt. Don’t close any credit cards (because your length of time matters). Have a good mix of credit.