In 1957, a beach-ball-shaped satellite hurtled into the sky and pierced the invisible line between Earth and space. As it rounded the planet, Sputnik drew an unseen line of its own, splitting history into distinct parts—before humankind became a spacefaring species, and after. “Listen now for the sound that will forevermore separate the old from the new,” one NBC broadcaster said in awe, and insistent that others join him. He played the staccato call from the satellite, a gentle beep beep beep.

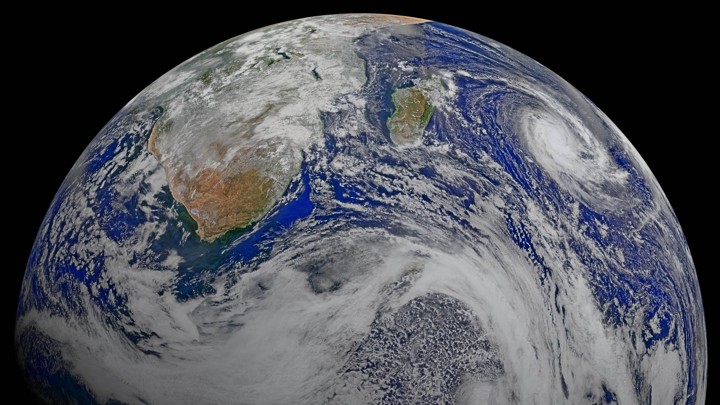

Decades later, we are not as impressed with satellites. There have been thousands of other Sputniks. Instead of earning front-page stories, satellites stitch together the hidden linings of our daily lives, providing and powering too many basic functions to list. They form a kind of exoskeleton around Earth, which is growing thicker every year with each new launch.

The newest additions come from SpaceX. The company launched 60 satellites into orbit Thursday night, the first batch of thousands of satellites that will someday beam internet down to Earth. The satellites traveled to space in a big, cozy stack. Once in orbit, they will fan out—“like spreading a deck of cards on a table,” according to Elon Musk—and unfurl solar arrays to soak up the sunlight they’ll use to power themselves. As of early Friday morning, all 60 satellites had come online.

Musk, SpaceX’s CEO, says the effort, named Starlink, will provide convenient and reliable internet service “ideally throughout the world.”

Sixty is just the beginning. Musk hopes to deploy as many as 12,000 satellites to furnish the constellation. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we’re launching at least on the order of 1,000 to 2,000 satellites a year,” he told reporters recently.

That’s a lot of satellites. Right now, about 5,000 are in orbit around Earth—in total. Only about 2,000 are still functioning. Nearly half belong to the United States, with China and Russia leading the pack with the rest. “I think within a year and a half, maybe two years, if things go well, SpaceX will probably have more satellites in orbit than all other satellites combined,” Musk said. “If things go according to plan—a big if, of course, but it is quite remarkable to think of that being the case.”

The launch puts Musk ahead of other entrepreneurs with their own internet-satellite ambitions. Jeff Bezos wants to launch thousands through a program under Amazon, and Greg Wyler, the head of OneWeb, which was established for this express purpose, deployed the company’s first six satellites in February.

SpaceX’s initial delivery of satellites is also a bit of a headache for a niche group of conservationists, the people who worry about the growing number of satellites and pieces of debris accumulating over Earth. They warn that a crowded orbit increases the risk of collisions, fast-moving impacts that would generate even more floating junk. A historian once told me that if an avalanche of crashes were to knock out the entire satellite infrastructure, “tentacles of disruption” would unfurl across the globe. Some experts even say that a packed orbit would make it more difficult for space missions to squeeze through and leave Earth altogether.

“The space environment isn’t easy to clean,” says Lisa Ruth Rand, a historian who studies orbital debris. “As difficult as it is to remediate damage on Earth from, say, an oil spill, imagine how difficult it would be to clean up a disaster in microgravity.”

Musk said SpaceX is “taking great pains to make sure there’s not an orbital-debris issue.” The newest satellites, he pointed out, orbit at an altitude low enough that allows them to become sucked back into Earth’s atmosphere within a year if they stop working. The satellites also receive radar information that tracks objects in orbit, allowing them to “automatically maneuver around any orbital debris.”

The fact that SpaceX is doing the kind of work historically done by national governments doesn’t seem as novel as it did even a few years ago. But the thought of a commercial company’s satellites outnumbering all the rest, and in such a short period of time, is rather astonishing. If extraterrestrial beings were to swing past Earth and check the tags on the artificial objects shrouding the planet, they might think the place belonged to SpaceX.