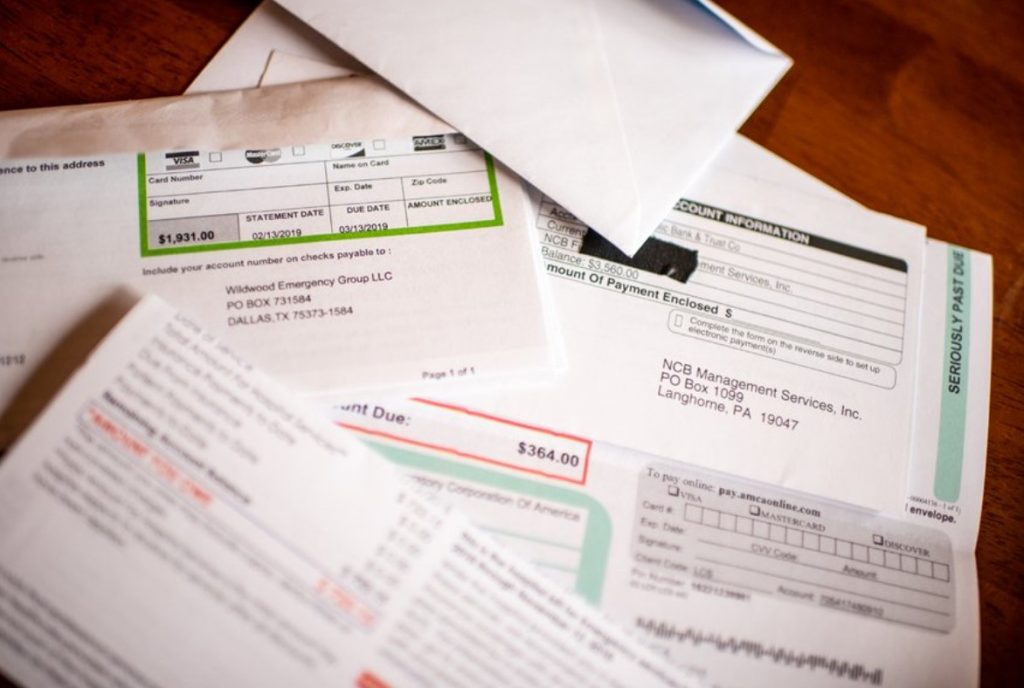

Although Americans’ overall medical debts have decreased in the decade since the Great Recession, medical bills now outweigh all other sources of debt combined as the largest contributor to personal debt in the U.S.

Based on a sample of debt listings reported to a single credit bureau between 2009-2020, researchers found average medical debt to be highest among those living in the South and in lower-income communities, according to a new study published in JAMA.

Further, the nationwide decline in medical debt that kicked off around 2013-2014 was greater in states that promptly chose to expand Medicaid in 2014 than in those that expanded a later year, the researchers wrote. Decreases in medical debt were lowest in non-expansion states, which frequently claimed the highest levels of medical debt to begin with.

“These estimates are consistent with studies that have used experimental methods to establish a causal link between Medicaid coverage and reductions in medical debt,” the researchers wrote in the study.

By the tail end of June 2020, individual Americans had a mean medical debt of $429—$39 more than the combined average of all other non-medical debts such as credit cards, utilities and phone bills, the researchers wrote.

Extrapolating their findings to the entire population would suggest that Americans’ total medical debt could be as high as $140 billion. However, the researchers warned against using this number as a reliable estimate due to limitations in their data, which included the use of consumer credit reports from just a single bureau (TransUnion) and the lack of a means to measure medical debts that weren’t reported to the bureau by third-party debt collectors.

The researchers also noted that their data would not reflect medical debts incurred during 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic, which along with accompanying financial hardships could have a sizeable impact on the country’s personal debts.

The mean per person stock of medical debt (defined as an individual’s total amount of unpaid medical debt) began at $750 in 2009 and peaked at $827 in 2010 before decreasing to 2020’s $429, the researchers found. The mean flow of medical debt (defined as the debt appearing on an individual’s credit report during the previous 12 months) began at $427 per person and landed at $311 in 2020.

Just under 18% of Americans had medical debt in collections, according to the study. For these individuals alone, the mean stock and flow was $2,424 and $2,396, respectively.

In the South, the U.S. Census region with the highest amount of medical debt, mean stock was $616 and 23.8% of individuals held medical debt. In the Northeast, where it was the lowest, mean stock was $167 with medical debt held by 10.8% of individuals.

Measuring mean stock by zip code income deciles saw a steady decline in medical debt with wealth, the researchers found. In the lowest zip code income decile, the mean stock of medical debt nationwide was $677—$551 higher than the $126 mean stock of the wealthiest decile.

Medicaid expansion appears to address a key social determinant of health

As for the impact of Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 saw their mean flow of medical debt decline 34% more than non-expansion states from 2013-2020. States that expanded after 2014 saw a 20.4% decline compared to non-expansion states.

Here the researchers noted that the non-expansion states’ poor residents were hit particularly hard by medical debts, with the mean flow increasing $206 from 2009-2020 for the lowest zip code income decile compared to a $12 decrease among the highest.

“The analysis shows that Medicaid expansion was associated with reductions in medical debt in collections,” the researchers wrote in the study. “Although the study design does not allow for causal interpretation, the absence of a meaningful association between Medicaid expansion and changes in nonmedical debt, and the stability of the estimates, controlling for economic and policy factors, reduce concerns about possible confounders.”

In an accompanying editorial, public health experts from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor stressed the negative health and social impacts that medical debts can have on individuals.

For the former, they wrote that although there is little data describing the downstream health effect of medical debt, “solid evidence” has painted wealth as a persistent social determinant of health in regard to individuals’ mortality, disability and illness recovery.

For the latter, inability to secure credit due to personal debt can disrupt access to food, housing, transportation and employment, impacts that can affect entire families and extend across generations, they wrote.

The study’s implication that medical debt is now the single largest contributing factor to these burdens underscores a pressing need to address these debts within the U.S. healthcare system, they wrote.

From a policy perspective, the current version of the ACA is still young and difficult to evaluate, they wrote. A number of studies have pointed to ACA-related improvements in coverage and other health disparities, yet data from its early years suggest that increased coverage facilitated by the law did not appear to produce a “noticeable” dip in medical debt bankruptcies, they wrote.

Still, the most recent findings “suggest that effective healthcare policies could lead to substantial reductions in overall medical debt. Further improvements will depend on sustained advocacy for universal access to affordable health care that will not saddle patients with inadequate health care or high out-of-pocket costs,” the policy experts wrote.