Inspired by the biomechanics of the manta ray, researchers at North Carolina State University have developed an energy-efficient soft robot that can swim more than four times faster than previous swimming soft robots. The robots are called “butterfly bots,” because their swimming motion resembles the way a person’s arms move when they are swimming the butterfly stroke.

“To date, swimming soft robots have not been able to swim faster than one body length per second, but marine animals—such as manta rays—are able to swim much faster, and much more efficiently,” says Jie Yin, corresponding author of a paper on the work and an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at NC State. “We wanted to draw on the biomechanics of these animals to see if we could develop faster, more energy-efficient soft robots. The prototypes we’ve developed work exceptionally well.”

The researchers developed two types of butterfly bots. One was built specifically for speed, and was able to reach average speeds of 3.74 body lengths per second. A second was designed to be highly maneuverable, capable of making sharp turns to the right or left. This maneuverable prototype was able to reach speeds of 1.7 body lengths per second.

“Researchers who study aerodynamics and biomechanics use something called a Strouhal number to assess the energy efficiency of flying and swimming animals,” says Yinding Chi, first author of the paper and a recent Ph.D. graduate of NC State. “Peak propulsive efficiency occurs when an animal swims or flies with a Strouhal number of between 0.2 and 0.4. Both of our butterfly bots had Strouhal numbers in this range.”

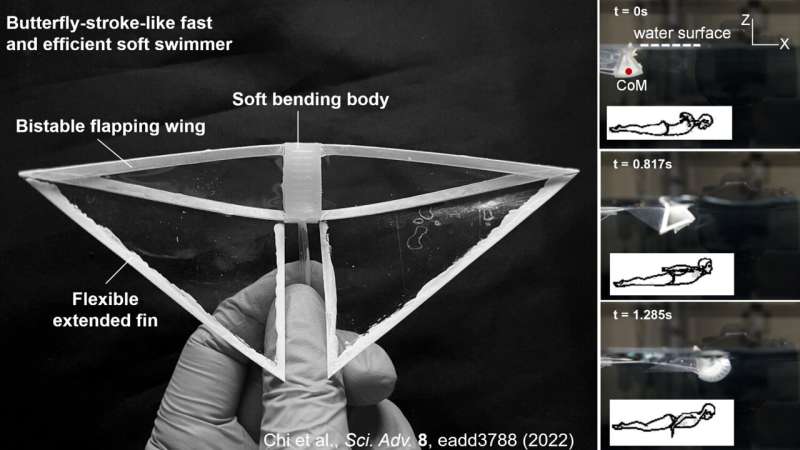

The butterfly bots derive their swimming power from their wings, which are “bistable,” meaning the wings have two stable states. The wing is similar to a snap hair clip. A hair clip is stable until you apply a certain amount of energy (by bending it). When the amount of energy reaches critical point, the hair clip snaps into a different shape—which is also stable.

In the butterfly bots, the hair clip-inspired bistable wings are attached to a soft, silicone body. Users control the switch between the two stable states in the wings by pumping air into chambers inside the soft body. As those chambers inflate and deflate, the body bends up and down—forcing the wings to snap back and forth with it.

“Most previous attempts to develop flapping robots have focused on using motors to provide power directly to the wings,” Yin says. “Our approach uses bistable wings that are passively driven by moving the central body. This is an important distinction, because it allows for a simplified design, which lowers the weight.”

The faster butterfly bot has only one “drive unit”—the soft body—which controls both of its wings. This makes it very fast, but difficult to turn left or right. The maneuverable butterfly bot essentially has two drive units, which are connected side by side. This design allows users to manipulate the wings on both sides, or to “flap” only one wing, which is what enables it to make sharp turns.

“This work is an exciting proof of concept, but it has limitations,” Yin says. “Most obviously, the current prototypes are tethered by slender tubing, which is what we use to pump air into the central bodies. We’re currently working to develop an untethered, autonomous version.”

The paper, “Snapping for high-speed and high-efficient, butterfly stroke-like soft swimmer,” will be published Nov. 18 in the open-access journal Science Advances. The paper was co-authored by Yaoye Hong, a Ph.D. student at NC State; and by Yao Zhao and Yanbin Li, who are postdoctoral researchers at NC State.