Metal-halide perovskites have quickly advanced in the last decade since their discovery as a semiconductor that outshines silicon in its conversion of light into electric current.

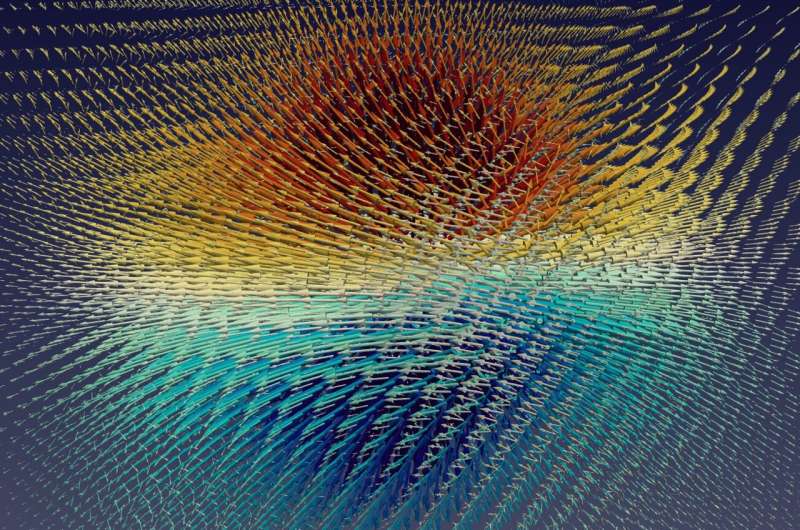

Simulations on TACC’s Frontera and Lonestar6 supercomputers have revealed surprising vortex structures in quasiparticles of electrons and atoms, called polarons, which contribute to generating electricity from sunlight.

This new discovery can help scientists develop new solar cells and LED lighting. This type of lighting is hailed as eco-friendly, sustainable technology that can reshape the future of illumination.

“We found that electrons form localized, narrow wave packets, which are known as polarons. These ‘lumps of charge’—the quasiparticle polarons—endow perovskites with peculiar properties,” said Feliciano Giustino, professor of Physics and W. A. ‘Tex’ Moncrief, Jr. Chair of Quantum Materials Engineering at the College of Natural Sciences and core faculty at the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences (Oden Institute) at UT Austin.

Giustino is a co-author of research on polarons discovered in halide perovskites published March 2024 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“These polarons show very intriguing patterns. The atoms rotate around the electron and form vortices that had never been observed before,” said Giustino, who also is the director of the Center for Quantum Materials Engineering at the Oden Institute.

The vortex structures of polarons may help the electrons remain in an excited state, which happens when a photon of light knocks into the compounds at the atomic level.

“We suspect that this strange vortex structure prevents the electron from going back to the unexcited energy level,” Giustino explained. “This vortex is a protected topological structure in the halide perovskite lattice material that remains in place for a long time and allows the electrons to flow without losing energy.”

Perovskite structures are a type of material known for over a century when Gustav Rose discovered the calcium titanium oxide perovskite CaTiO3 in 1839. More recently, in 2012 Giustino was working with the group of Oxford University scientist Henry Snaith who discovered a new type of perovskite called halide perovskites—where instead of oxygen there are halogens, elements that form salts when they react with metals.

“It turns out that halide perovskites in solar cells show exceptional energy conversion efficiency,” Giustino said.

In comparison, the top efficiency in silicon is about 25 percent, meaning that out of all the energy coming from the sun, one quarter is converted to electricity. To reach 25 percent efficiency, silicon took about 70 years of development. Halide perovskites, on the other hand, managed to reach 25 percent efficiency within just 10 years.

“This is a revolutionary material,” Giustino said. “That explains why many research groups working on photovoltaics have moved to perovskites, because they are very promising. Our contribution looked at the fundamentals using computational methods to delve into the properties of these compounds at the level of individual atoms.”

For the study, Giustino used allocations on the Lonestar6 and Frontera supercomputers awarded by the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC), as well as U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) supercomputers at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC).

“This research is part of a project sponsored by the Department of Energy that has been going on for several years with the support of TACC and in particular Frontera, where we developed methodologies to study how electrons interact with the underlying atomic lattice,” Giustino said.

For example, Giustino said in the case of halide perovskites, the large polarons they found required simulation cells of about half a million atoms, which is not possible to study with standard methods.

To manage these calculations on a supercomputer, Giustino and his collaborators at Austin and beyond developed EPW, an open-source Fortran and message passing interface code that calculates properties related to electron-phonon interaction. The EPW code specializes in studying how electrons interact with vibrations in the lattice of a solid, which causes the formation of polarons. This code is currently developed by an international collaboration led by Giustino.

“Our collaboration with TACC is more than using advanced computing resources,” Giustino said. “The most important part is the interaction with the people. They’ve been essential in helping us profile the code and making sure we avoid bottlenecks by applying profiling tools that help us study performance decreases. Much of the work happening on the EPW code is in collaboration with TACC experts that help us improve scaling the code to get optimal performance on the supercomputers.”

“The CSA work between my group and TACC to optimize the EPW code allows us to push the frontiers of what one can investigate in understanding and discovering new, important materials. It’s a combination of theory, algorithms, and high performance computing with much back and forth with our colleagues at TACC to make sure that we use the supercomputers in the most viable way possible,” Giustino said.

Another possible application is the development of ferroelectric memory devices, computer memory that can be more compact. In it, information is encoded by the vibration of atoms in a crystal under an applied electric field.

“Investment in high-performance computing and future computing is essential to science,” Giustino concluded. “It requires large investments like the ones that sustain and expand facilities like TACC.”