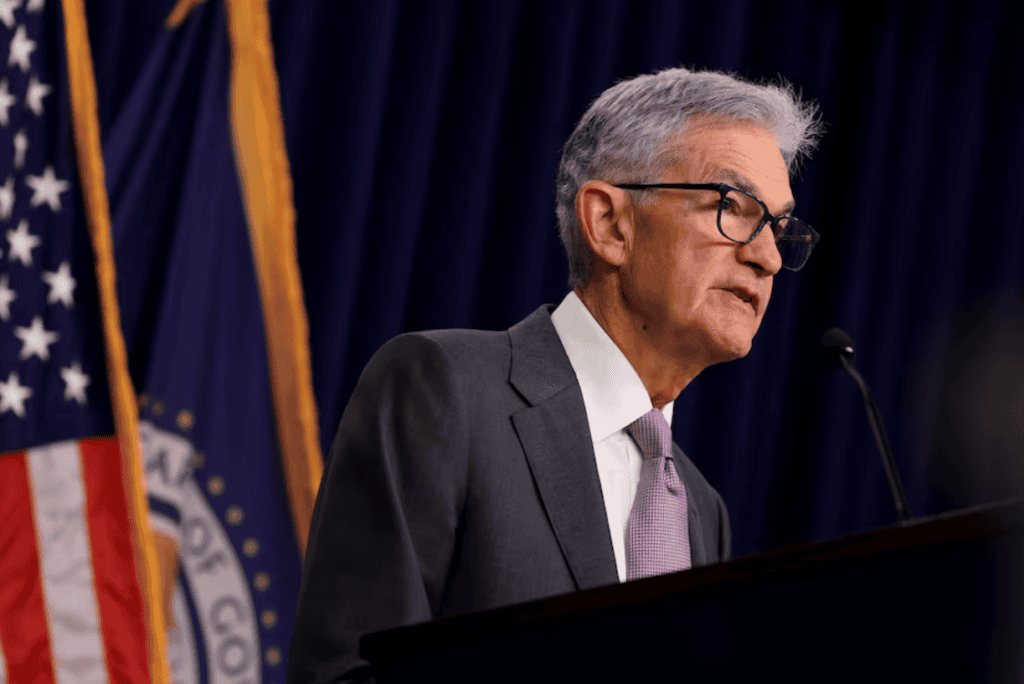

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said on Wednesday interest rates could be cut as soon as September if the U.S. economy follows its expected path, putting the central bank near the end of a more than two-year battle against inflation but square in the middle of the nation’s presidential election campaign.

The Fed ended its latest two-day policy meeting with a decision to hold its benchmark interest rate steady in the 5.25%-5.50% range that was set a year ago, but its statement softened the description of inflation and said the risks to employment were now on a par with those of rising prices – neutral language that opens the door for rates to fall after more than two years of tightening credit.

Powell pushed the message even further forward in his post-meeting press conference, noting that price pressures were now easing broadly in the economy – what he called “quality” disinflation – and that if coming data evolves as anticipated, support for cutting rates will grow.

“If we were to see inflation moving down … more or less in line with expectations, growth remains reasonably strong, and the labor market remains consistent with current conditions, then I think a rate cut could be on the table at the September meeting,” he said.

Republican lawmakers warned in a hearing with Powell in July that a rate cut at the Sept. 17-18 meeting, seven weeks before the U.S. elections, could be seen as a politicized move – highlighting progress on inflation and offering the mood-lifting promise of cheaper credit and home mortgages in the near future.

The Fed chief, in response to a question from a reporter on Wednesday, said the central bank’s only consideration was the state and direction of the economy and the progress of inflation back to its 2% annual target, not the political calendar or any party’s fortunes.

“This is how we think about it. This is what we do,” Powell said.

Some Fed policymakers even discussed the logic of cutting rates at this session, Powell said, but “the sense of the (policy-setting) committee was not at this meeting, but as soon as the next meeting depending on how the data come in.”

SETTING THE STAGE

Powell’s remarks on Wednesday affirmed what investors had come to see as a near certainty that the Fed would pivot in September from an era of restrictive, some would say punishing, interest rates, to a steady easing of credit policy that would see inflation finish the journey to the 2% level without undue damage to the labor market.

Powell said he felt such a “soft landing” was in view, with data that is “not signaling a weak economy. It is also not signaling an overheating economy,” he noted.

The Fed’s new policy statement, opens new tab took that optimistic outlook on board, noting that “there has been some further progress toward the (Federal Open Market) Committee’s 2% objective,” while the unemployment rate, at 4.1%, “remains low.”

The central bank uses the personal consumption expenditures price index for its 2% inflation target. The PCE price index rose 2.5% in June after exceeding 7% in 2022, and the month-to-month readings recently have shown it even closer to the target.

Investors saw Powell’s comments as clearly setting the stage for a reduction in borrowing costs at the Fed’s Sept. 17-18 meeting.

“Listening to him speak, it’s clear they’re all locked and loaded for a September rate cut and they’re going to maintain their optionality,” said Mark Malek, chief investment officer at SiebertNXT.

Interest rate futures, stocks and Treasury bonds all rallied hard on Powell’s remarks, so much so that the probability of a first cut in September being as large as half a percentage point jumped to about 13% from about 5% before he began speaking, according to CME Group’s FedWatch tool. Powell, however, said a 50-basis-point cut was not something under active consideration.

While Fed officials are wary of any actions that could mar their data-not-politics approach to setting monetary policy, the steady drop in inflation in recent months prompted a broad consensus that the inflation battle was near an end.

Inflation, the Fed said in its unanimously approved statement, was now just “somewhat elevated,” a key downgrade from the assessment that it has used for nearly three years that it was “elevated.”

The Fed’s policy statement also removed standing language that it was “highly attentive to inflation risks,” and replaced it with an acknowledgement that policymakers were now “attentive to the risks to both sides of its dual mandate,” which includes a charge from Congress to maintain maximum employment consistent with stable prices.

So far the economy “has continued to expand at a solid pace,” the Fed said in its statement, and while “job gains have moderated,” the unemployment rate “remains low.”

But the jobless rate has been rising, and policymakers have put more focus of late on avoiding the sort of sharp rise in unemployment often associated with high interest rates and slowing inflation.