One of Wall Street’s favorite tools could be deepening the growing chasm between America’s rich and poor.

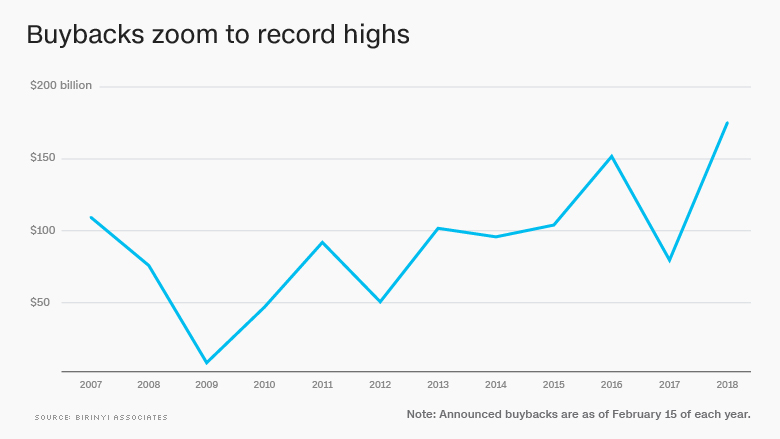

Since 2008, companies in the United States have spent a stunning $5.1 trillion to buy back their own stock, according to Birinyi Associates. Shareholders love buybacks, because they boost stock prices by making shares scarcer.

Buybacks have exploded in 2018 thanks to windfall from the Republican tax law. American companies including Wells Fargo (WFC) and Cisco (CSCO) have showered Wall Street with $214 billion of stock buyback announcements so far this year, according to research firm TrimTabs.

But critics argue Corporate America’s fascination with stock buybacks has come at a real cost to American workers. Instead of focusing on short-term rewards for shareholders, they say companies should make long-term investments by retraining workers, ramping up benefits and boosting wages.

“Stock buybacks have been a prime mode of both concentrating income among the richest households and eroding middle-class employment opportunities,” said William Lazonick, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell who has studied the impact of stock buybacks.

Between 2007 and 2016, companies in the S&P 500 spent 54% of their profits on stock buybacks, Lazonick says.

During that time, capital spending on job-creating items like new plants has languished. Some companies have even taken on extra debt to pay for their stock buyback habit.

“Buybacks have a negative impact on inequality and on the economy,” former Labor Secretary Robert Reich told CNNMoney.

‘Smoke and mirrors’

By eliminating shares, buybacks inflate a critical measure of profitability: earnings per share. It’s a financial engineering trick. Companies can appear more profitable even if their profits aren’t growing.

Buybacks are “smoke and mirrors,” Yale professor Robert Shiller told CNNMoney.

More than 40% of total EPS growth between 2009 and mid-2017 is from share repurchases, according to estimates by Christopher Cole, who runs a hedge fund called Artemis Capital Management.

“Buybacks are not resulting in jobs or new factories. They are not benefiting the middle class,” said Cole.

A rising stock market can help many Americans by increasing the value of retirement plans and providing a boost of confidence in the overall economy.

About 52% of families owned stocks directly or indirectly through retirement plans like 401(k)s in 2016, according to the Federal Reserve.

But the rich benefit more than the rest of the country. That’s because the top 10% of households owned 84% of all stocks in 2016, according to NYU professor Edward Wolff.

“The gains go disproportionately to the top,” Wolff said in an interview. Stock buybacks “will just exacerbate existing wealth inequality,” he said.

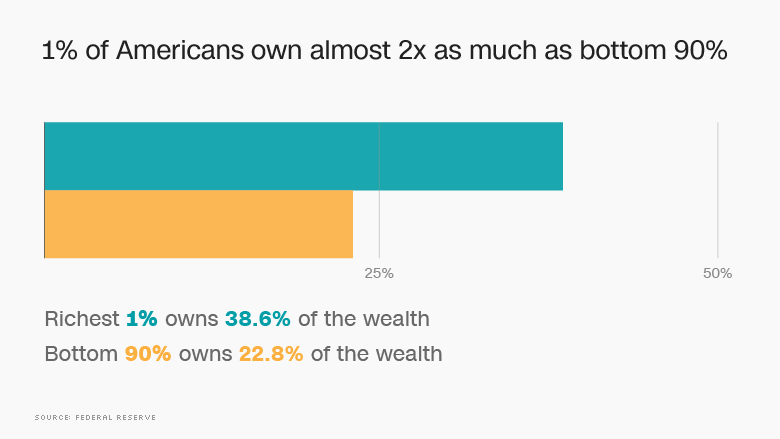

Top 1% owns way more than bottom 90%

The inequality problem has grown worse in America.

The top 1% of families earned a record-high 23.8% of overall income in 2016, the Fed estimates. The bottom 90% of families made less than half of the country’s income, down from 60% in 1992.

Paychecks tell only part of the story. Including stocks and other assets, the richest 1% of families held a record-high 38.6% of the wealth in 2016, according to the Fed. That’s nearly twice as much as the bottom 90%.

The good news is many companies have decided to share some of their tax windfall with workers, most notably through one-time bonuses paid out by Comcast (CMCSA), Disney (DIS), Bank of America (BAC) and dozens of others.

The White House estimates that 3 million workers have benefited from the one-time bonuses. That’s real money that can boost the economy and help Americans pay down debt or save for a rainy day.

Other major companies, such as Walmart (WMT) and Wells Fargo, have raised wages for workers, a more lasting move that could help improve the income inequality. A handful of companies, including Boeing (BA), FedEx (FDX), Apple (AAPL) and JPMorgan Chase (JPM), have announced plans to invest more than 100% of their tax savings on workers, job creation and boosting local communities, according to JUST Capital, a nonprofit founded by Arianna Huffington, hedge fund billionaire Paul Tudor Jones and others.

Yet the money devoted to workers pales in comparison with the buyback bonanza.

So far just 6% of the corporate windfall from the tax cuts have gone to workers in the form of pay hikes, bonuses and other investments, according to an analysis by JUST Capital. That is even worse than the 13% that analysts polled by Morgan Stanley expect to go to workers.

Capital owners versus workers

Some think the focus on share buybacks is misplaced. They argue that the money ultimately belongs to shareholders — and those shareholders include workers and retirees.

Everyone can agree that buybacks are a more productive use for extra cash then letting it sit in an overseas bank account where it earns virtually nothing. Buybacks free up capital that can then be used by shareholders to make investments that do create new jobs.

“I’m skeptical that businesses are leaving money on the table,” said PNC chief economist Gus Faucher.

Buybacks also signal confidence in the business and the stock price. That confidence can translate to stronger and higher wages.

Although Faucher doesn’t think buybacks are the “cause” of inequality, he concedes they are a “symptom” of an economy that has tilted more and more in favor of shareholders. He noted that corporate profits as a share of the overall economy have gone up significantly over the past three decades.

“The benefits of economic growth are going towards capital owners instead of workers,” Faucher said.

Should buybacks be banned?

Stock buybacks used to be a murky area, with many claiming they were a form of market manipulation. But the SEC ruled in 1982 that companies could repurchase vast amounts of their own stock.

Criticism of buybacks is building in the wake of the tax law. Senate Democrats published a report on Wednesday strongly criticizing the buyback boom as evidence that tax savings aren’t trickling down to workers.

Lazonick predicted that Democrats in Congress may soon introduce a bill to crackdown on or even ban buybacks.

“There is no reason buybacks should be considered anything but illegal manipulation of stock,” said Reich.

But given how much the stock market relies on buybacks, such a move could be difficult politically. After all, no lawmaker wants to get blamed for spooking the market.

Wall Street would cry foul, arguing Washington is trying to tell corporations how to spend their money.

Lazonick argued that banning buybacks would not hurt long-term investors because it would force companies to invest in the future, instead of catering to short-term shareholders.

“Workers, taxpayers and society as a whole will benefit,” he said.