Debates over privacy have plagued Facebook for years.

But the news that Cambridge Analytica, a political data firm that worked on President Trump’s 2016 campaign, was able to gain access to private data through the social network has sparked an unusually strong reaction among its users.

The hashtag #DeleteFacebook appeared more than 10,000 times on Twitter within a two-hour period on Wednesday, according to the analytics service ExportTweet. On Tuesday, it was mentioned 40,398 times, according to the analytics service Digimind.

Cher was one such deserter, writing on Twitter that the decision to quit Facebook, although “very hard,” was necessary because she loves the United States.

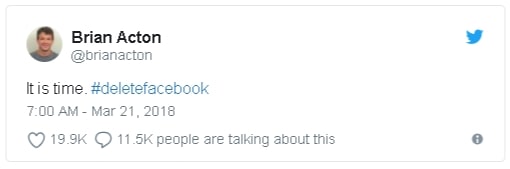

Brian Acton, a co-founder of the WhatsApp messaging service, told his tens of thousands of followers on Tuesday to delete Facebook. The social network acquired WhatsApp in a $19 billion deal in 2014.

For people who aren’t celebrities or billionaires, the decision to abandon Facebook came reluctantly, because the platform often served as their sole connection to certain relatives, friends and professional opportunities.

Here, some newly Facebook-free users of social media discuss why they left.

Richard H. Perry

A filmmaker in Los Angeles

For a long time now, Mr. Perry had wanted to leave Facebook.

He never felt comfortable knowing that the company had access to much of his personal information. In the months before the 2016 presidential election, he watched the social network become what he called “a garbage platform of ads and weird reposted articles and people that you care about exposing themselves as racists.”

But Facebook was also where Mr. Perry promoted his films, where he posted ads seeking help on the set, and where he communicated with colleagues and a “massive number” of his friends and relatives.

Until he heard about Cambridge Analytica.

“I suspected this stuff was going on, but this is the first time it’s been plainly exposed,” he said. “It seems so malicious, and Facebook seems so complicit all the way up and down, like it doesn’t care about its users.”

Mr. Perry, 39, has since deleted his profile and plans to switch to Twitter and Instagram for his social media needs.

“It was an easy decision,” he said. “It’s not going to be the end of the world.”

Dan Clark

A retired Navy veteran in Maine

Mr. Clark kept one Facebook account to chat with friends and a separate account to keep tabs on members of his family nationwide. This week, he deleted both.

“Facebook was the main platform I used to keep in touch with all of them, and it was a difficult decision to give it up,” he said. “But you have to stand for something, so I just put my foot down and said enough is enough.”

Mr. Clark, 57, said he had already been angry with Facebook for censoring some of his posts, which he said expressed his staunchly conservative views but were “never evil or putting anybody down.” He could not abide the idea that his personal information was also being sold or given away without his consent.

Before cutting the cord, Mr. Clark posted on Facebook inviting his contacts to ask him for his personal phone number. More than 100 people reached out within three days.

“There are just so many ways nowadays to stay in contact: phones, email, instant message, Gab, which is a social network that doesn’t censor anything,” he said. “Facebook is more obsolete than people would think.”

Alexandra Kleeman

A writer in Staten Island

Her first experience with fake news — a Facebook post claiming that Pope Francis had endorsed Mr. Trump’s candidacy — altered the way Ms. Kleeman looked at Facebook.

“It changed the psychological and emotional feel of the platform for me,” she said. “I don’t have a great feeling when I log in.”

The Cambridge Analytica scandal led her to remove the Facebook app from her phone. “I’m not going to give them my engagement clicks,” Ms. Kleeman, 32, said. But she is keeping the messaging function open for professional purposes and will continue using Instagram.

She doesn’t mind the idea that some personal data can be made public — she used to have a blog, she said.

“But the idea that my data could be used for purposes that I expressly don’t want, that freaks me out.”

Paul Musgrave

An assistant professor in Amherst, Mass.

Twitter makes Mr. Musgrave feel depressed about the world, but Facebook is the social media platform he is trying to abandon.

As a political science teacher at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Mr. Musgrave, 36, feels a professional responsibility to keep abreast of the news and academic chatter hurtling at him in the form of tweets.

Facebook was more valuable to him as a “low-key, offstage networking tool,” a “replacement for end-of-year family newsletters” that allowed him to “passively keep up with people,” he said. He joined the platform more than a decade ago and before that had been a member of Friendster, a precursor to Facebook.

But in 2016, while helping his mother during her campaign for a government position in Indiana, Mr. Musgrave discovered a “poisonous swamp” of content on the site. The Cambridge Analytica findings were even more disturbing, he said.

“This is a company that has Orwellian levels of data about us, truly Big Brother-level, but it’s behaving as if it has no social responsibility and is a purely neutral medium of communication,” he said. “That’s what’s really been scary.”

Having deactivated his Facebook account, with plans to delete it, he now worries about connecting with people who use the social network as their main conduit of communication.

“I’m definitely pruning myself away from some of those really important branches,” he said. “I watch my own students try to navigate the world of apps and smartphones, and even they don’t really know how the internet works outside these enclosed garden spaces.”

Ben Greenzweig

An entrepreneur in Westchester, N.Y.

Once Mr. Greenzweig confirms that the 1,195 photos and 85 videos in his Facebook profile have downloaded, he plans to delete the account he has maintained for nearly a decade.

Mr. Greenzweig, 40, said the Cambridge Analytica news was “the last straw.”

“We have surpassed the tipping point, where the benefit now fails to outweigh the cost,” he said. “But I will definitely miss what the promise of Facebook used to be — a way to connect to community in a very global and local context.”

A year ago, Mr. Greenzweig was an “extraordinarily active” Facebook user who juggled conversations with friends, managed several groups, took out ads for his business and maintained professional contacts.

But on Tuesday night, in his final post, he asked his network to connect with him through email, LinkedIn, Twitter or phone.

“See everyone in the real world,” he wrote.