For decades, scientists have debated the cause of the popping sound when we crack our knuckles. Using computer models, a research team from France may have finally reached the answer.

As the authors state in the new paper published today in Scientific Reports, the sound of knuckles cracking is caused by a “collapsing cavitation bubble in the synovial fluid inside a metacarpophalangeal joint during an articular release.” More simply, it’s the sound of microscopic gas bubbles collapsing—but not fully popping—inside the finger joint. Scientists first proposed this theory nearly 50 years ago, but this latest paper used a combination of lab experiments and a computer simulation to bolster the case.

Seems weird, but scientists have been investigating this bodily quirk since the early 1900s, and they haven’t been able to reach consensus on the cause of the popping sound. The seemingly endless debate is the result of unconvincing experimental evidence, and the difficulty in visualizing the process in action: The whole phenomenon takes only about 300 milliseconds to unfold. What scientists have agreed upon, however, is that knuckle cracking is not something everyone is able to do, not every finger can produce the popping sound, and it takes about 20 minutes before a knuckle can be cracked again.

To help clear things up, and to add more support to existing experimental data, V. Chandran Suja and Abdul Bakarat from École Polytechnique in France took geometric representations of the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP), where the popping happens, and converted them into mathematical equations that powered computer simulations of knuckle cracking. Or more specifically, computer simulations that showed what goes on in our fingers just prior to that popping sound.

“Mathematical modeling is particularly useful because [real-time] imaging is not sufficiently rapid to capture the phenomena involved,” Bakarat told Gizmodo. “Another advantage of the modeling is that it allows varying one parameter at a time and therefore permits determining which parameters are truly important in determining the behavior. In this regard, we found that the parameter that has the most effect on the sound generated by knuckle cracking is how hard you pull on the knuckle. How fast you pull, the geometry of the joint, and the viscosity of the fluid (which changes with age) do not have a very strong effect.”

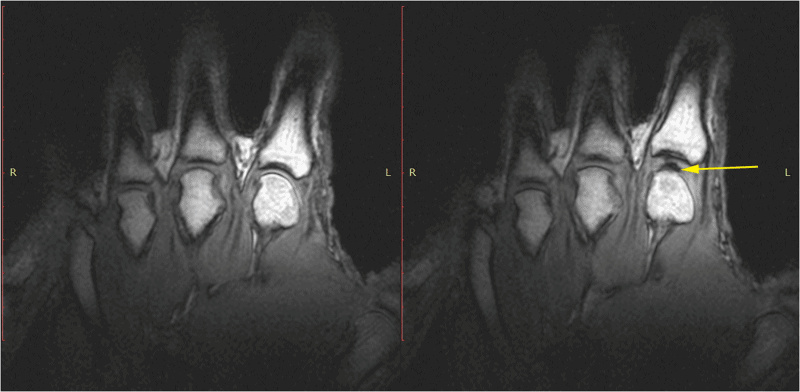

The models showed that when the joint undergoes a certain amount of stress, the resulting pressure changes in the joint fluid causes the collapse of microscopic gas bubbles within the synovial joint fluid. This theory was first proposed by scientists from the University of Leeds in 1971, but in 2015, a PLoS One paper led by Greg Kawchuk from the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine used MRI scans to show that gas bubbles remained in the fluid even after the knuckles were cracked. So instead of collapsing bubbles causing the popping sound, Kawchuk’s team said it was the sudden growth of bubbles that produced the noise.

But as Suja and Bakarat show, this is not a deal-breaking contradiction. According to their models, only a partial collapse of the bubbles is needed to make the pop, and that’s why bubbles can still be seen even after knuckle cracking. And to prove their point even further, the researchers recorded the sound of knuckles cracking from three test subjects, and compared the digital acoustic waves to those mathematically produced by the computer simulation. The two acoustic waveforms were extremely similar, suggesting that Suja and Bakarat’s model is providing an accurate representation of knuckle cracking, and that the cause of the popping noise is indeed the sound of bubbles collapsing.

In terms of limitations, Bakarat said his team made a number of assumptions in the study, including the presence of only a single bubble, that the bubble is perfectly spherical, that the joint has an idealized, common shape, among others. “Furthermore, a limitation of the study is that we do not model the formation of the cavitation bubble in the synovial fluid but only bubble collapse,” he said. “A possible future direction of this work is to extend the modeling to include the phase of bubble formation.”

Greg Kawchuk, the lead author of the 2015 paper, said Suja and Barakat “should be congratulated” for designing a mathematical model that creates a theoretical pre-existing bubble. He thought it was interesting that other phenomena may be involved in between the frames of the MRI video published in his earlier study. But he believes the new study doesn’t completely solve the knuckle cracking mystery.

“First, it must be emphasized that the work presented in this new study is a mathematical model that has not yet been validated by physical experimentation—we do not yet know if this occurs in real life,” Kawchuk told Gizmodo. “Second, although the authors of the paper demonstrated that the theoretical sounds produced by a theoretical bubble collapse were similar to actual sounds produced in knuckle cracking, the authors did not test the opposing circumstance proposed previously in the literature by asking, ‘what acoustics could be generated from bubble formation?’”

Which is an excellent point—one that Bakarat himself admitted was a limitation to the research. For all we know, rapid bubble formation may be producing a very similar knuckle-cracking sound, but the new study didn’t go there.

“As such, the impact of this new study is diminished by having investigated only one possibility (collapse of a pre-formed bubble) and disregarding other alternative phenomenon such as bubble formation, multiple formation/collapse events and the lingering issue of large volumes of gas in the joint following sound production that have been visualized by many investigators,” said Kawchuk.

This topic may seem trivial, Kawchuk said, but he believe this issue has potential importance to healthcare—it could reveal insights into preserving joint health and joint mobility on account of disease and increasing age.

As to whether or not knuckle cracking is unhealthy, this latest study doesn’t speak to that (and neither Bakarat nor Kawchuk were comfortable in answering this question). But in 2015, Robert D. Boutin from the University of California, Davis did some research showing that the habit produced no immediate pain, swelling, or disability among habitual knuckle crackers, nor among those who rarely, if ever, do it. Boutin added that “further research will need to be done to assess any long-term hazard—or benefit—of knuckle cracking,”