Many diversified investors are now discovering—after a market downdraft—that they are, in fact, largely tech investors.

That’s because of the dominance of the tech sector, whose prominence has swelled in indexes weighted by market cap. Technology stocks accounted for more than 25% of the Standard & Poor’s 500 index at the end of February. And just five stocks — Apple (ticker: AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), Amazon.com (AMZN), Google parent Alphabet (GOOGL), and Facebook (FB)—accounted for 14.4%, dwarfing entire sectors like industrials.

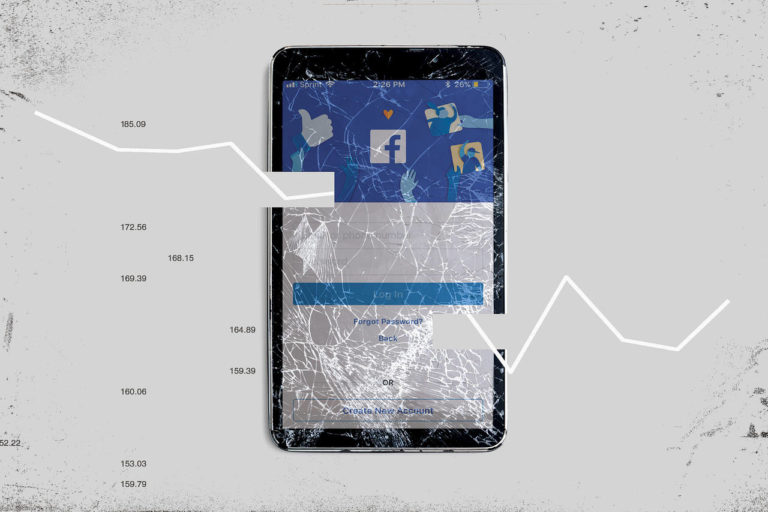

Reports two weeks ago about Facebook data and privacy concerns started a cascading effect among tech stocks, which have since fallen 6.3%, shedding $380 billion in value. And that doesn’t even include Amazon, which is classified as a consumer discretionary stock. Amazon fell 7% in just three days last week.

When those stocks lost their footing, it had an outsize effect on the overall S&P 500, and exposed the risks of making too large a bet in any one area. Financial stocks, for instance, rose above 22% of the index at the end of 2006, and we all know how that ended.

People who casually invest their 401(k)s in market-tracking indexes “think they are diversified, but in fact with tech such a dominant sector in the index, the overlap and sector concentration is significantly higher than they realize,” says John Petrides, portfolio manager at Point View Wealth Management.

On the way up, the tech rally made even the most passive investors look like geniuses. Cheap index-tracking funds weighted by market cap have benefited from a self-reinforcing pattern; as tech stocks outperformed, they became a larger portion of the total fund, and their gains flattered the results of the larger index.

That same dynamic makes the downside steeper, however.

“This has been my argument against indexing forever,” says Dan Wiener, chairman of Adviser Investments and an expert on low-cost fund strategies. “You are typically buying the stuff that’s gone up the most because the companies that have the greatest market caps are the ones that sit at the top of these indexes.”

“It’s the wisdom of the crowd and I don’t always think the wisdom of the crowd is that smart,” he says.

Some mutual fund managers—who have seen their business eaten away by index funds in the past decade—see an opportunity in the current confusion. “I was talking with a manager yesterday who was saying ‘This is precisely why you want active managers,’ ” says Tony Thomas, a Morningstar analyst who covers equity portfolio managers. “The manager said ‘We can try to anticipate these things. This gives us a chance to do our due diligence and adjust our weighting. Passive investors don’t have that luxury.’ ”

But it turns out that most active managers are even more exposed to tech than the benchmarks they track.

By October, large-cap, long-only mutual funds had an average of 30.3% of their holdings in technology stocks, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Since then, they’ve cut back slightly, with their most recent holdings showing a 29.4% weighting.

“Were fund managers prepared for this? No, in a word,” says Savita Subramanian, the head of U.S. equity strategy at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

It’s hard to blame them. Tech stocks have been fantastic investments, rising at an 18.5% annualized rate since the start of 2015, versus 10.2% for the S&P 500.

And unlike past euphorias—tech in 1999, banks in the mid-2000s, or energy during oil peaks—it has been driven by strong fundamental performance.

The dot-com bust is particularly instructive here. In December 1999, tech made up 29% of the S&P 500, but just 13% of the index’s earnings growth. Now tech makes up a quarter of the index and contributes 23% of the earnings growth, an indication that its sector weight is in line with its economic value, says Michael Arone, the chief investment strategist for State Street Global Advisors.

In the coming quarter, tech stocks are expected to grow earnings 22%, versus 17% for the broader S&P 500, Arone says.

Still, volatility may persist for high-profile companies like Facebook, whose chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, is expected to testify before Congress.

Subramanian says that the heavy tech holdings in mutual funds could make it harder to slow a selloff, because “the marginal buyer is already overweight the stocks.”

Investors worried about the prominence of companies like Facebook, Amazon, and Alphabet in their portfolios have several options. They can buy less sexy tech names that generate tons of cash and offer strong dividends, Subramanian suggests. Companies like Cisco Systems (CSCO) and Intel (INTC) would fit the bill.

Passive investors who want to avoid the overconcentration risk from cap-weighted indexes can buy funds that own equal proportions of each stock in an index like the Guggenheim S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF (RSP). And investors looking for growth without so many big tech names could buy the Primecap Odyssey Growth Fund (POGRX), one of Wiener’s favorites. The fund holds a diverse portfolio that includes tech stocks like Alibaba Group Holding (BABA), but is less exposed to other popular names that have come to dominate the market.

“They have a high-tech weighting, but it’s not the same high-tech weighting that you find in an index,” he says.

International indexes can also help. Apple sits atop the MSCI World Index, but overall that index is less exposed to tech than its U.S. counterpart, with an 18% allocation to the sector. “Indexes outside the U.S. are far more balanced across sectors,” says Jim Ayer, portfolio manager for Oppenheimer International Equity Fund (QIVAX).