Losing just one night of sleep led to an immediate increase in beta-amyloid, a protein in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease, according to a small, new study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. In Alzheimer’s disease, beta-amyloid proteins clump together to form amyloid plaques, a hallmark of the disease.

While acute sleep deprivation is known to elevate brain beta-amyloid levels in mice, less is known about the impact of sleep deprivation on beta-amyloid accumulation in the human brain. The study demonstrates that sleep may play an important role in human beta-amyloid clearance.

“This research provides new insight about the potentially harmful effects of a lack of sleep on the brain and has implications for better characterizing the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease,” says George F. Koob, PhD, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), in a release. NIAAA is part of the National Institutes of Health, which funded the study.

Beta-amyloid is a metabolic waste product present in the fluid between brain cells. In Alzheimer’s disease, beta-amyloid clumps together to form amyloid plaques, negatively impacting communication between neurons.

Led by Ehsan Shokri-Kojori, PhD, and Nora D. Volkow, MD, of the NIAAA Laboratory of Neuroimaging, the study is now in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Volkow is also the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse at NIH.

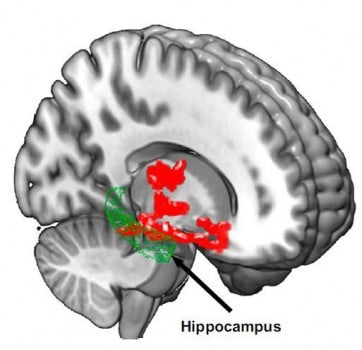

To understand the possible link between beta-amyloid accumulation and sleep, the researchers used positron emission tomography (PET) to scan the brains of 20 healthy subjects, ranging in age from 22 to 72, after a night of rested sleep and after sleep deprivation (being awake for about 31 hours). They found beta-amyloid increases of about 5% after losing a night of sleep in brain regions including the thalamus and hippocampus, regions especially vulnerable to damage in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

In Alzheimer’s disease, beta-amyloid is estimated to increase about 43% in affected individuals relative to healthy older adults. It is unknown whether the increase in beta-amyloid in the study participants would subside after a night of rest.

The researchers also found that study participants with larger increases in beta-amyloid reported worse mood after sleep deprivation.

“Even though our sample was small, this study demonstrated the negative effect of sleep deprivation on beta-amyloid burden in the human brain. Future studies are needed to assess the generalizability to a larger and more diverse population,” says Shokri-Kojori.

It is also important to note that the link between sleep disorders and Alzheimer’s risk is considered by many scientists to be “bidirectional,” since elevated beta-amyloid may also lead to sleep disturbances.