The first human corneas have been 3D printed by scientists at Newcastle University, UK.

It means the technique could be used in the future to ensure an unlimited supply of corneas.

As the outermost layer of the human eye, the cornea has an important role in focusing vision.

Yet there is a significant shortage of corneas available to transplant, with 10 million people worldwide requiring surgery to prevent corneal blindness as a result of diseases such as trachoma, an infectious eye disorder.

In addition, almost 5 million people suffer total blindness due to corneal scarring caused by burns, lacerations, abrasion or disease.

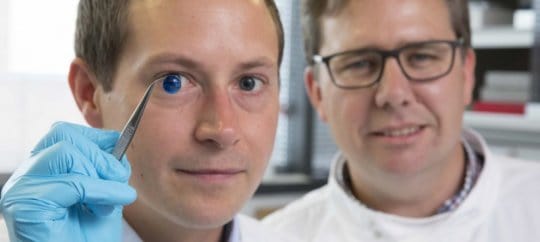

The proof-of-concept research, published today in Experimental Eye Research, reports how stem cells (human corneal stromal cells) from a healthy donor cornea were mixed together with alginate and collagen to create a solution that could be printed, a ‘bio-ink’.

Using a simple low-cost 3D bio-printer, the bio-ink was successfully extruded in concentric circles to form the shape of a human cornea. It took less than 10 minutes to print.

The stem cells were then shown to culture — or grow.

Che Connon, Professor of Tissue Engineering at Newcastle University, who led the work, said: “Many teams across the world have been chasing the ideal bio-ink to make this process feasible.

“Our unique gel — a combination of alginate and collagen — keeps the stem cells alive whilst producing a material which is stiff enough to hold its shape but soft enough to be squeezed out the nozzle of a 3D printer.

“This builds upon our previous work in which we kept cells alive for weeks at room temperature within a similar hydrogel. Now we have a ready to use bio-ink containing stem cells allowing users to start printing tissues without having to worry about growing the cells separately.”

The scientists, including first author and PhD student Ms Abigail Isaacson from the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, also demonstrated that they could build a cornea to match a patient’s unique specifications.

The dimensions of the printed tissue were originally taken from an actual cornea. By scanning a patient’s eye, they could use the data to rapidly print a cornea which matched the size and shape.

Professor Connon added: “Our 3D printed corneas will now have to undergo further testing and it will be several years before we could be in the position where we are using them for transplants.

“However, what we have shown is that it is feasible to print corneas using coordinates taken from a patient eye and that this approach has potential to combat the world-wide shortage.”