Nearsightedness, or myopia, is an increasing problem around the world. There are now twice as many people in the US and Europe with this condition as there were 50 years ago. In East Asia, 70 to 90 percent of teenagers and young adults are nearsighted. By some estimates, about 2.5 billion of people across the globe may be affected by myopia by 2020.

Eye glasses and contact lenses are simple solutions; a more permanent one is corneal refractive surgery. But, while vision correction surgery has a relatively high success rate, it is an invasive procedure, subject to post-surgical complications, and in rare cases permanent vision loss. In addition, laser-assisted vision correction surgeries such as laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) still use ablative technology, which can thin and in some cases weaken the cornea.

Columbia Engineering researcher Sinisa Vukelic has developed a new non-invasive approach to permanently correct vision that shows great promise in preclinical models. His method uses a femtosecond oscillator, an ultrafast laser that delivers pulses of very low energy at high repetition rate, for selective and localized alteration of the biochemical and biomechanical properties of corneal tissue. The technique, which changes the tissue’s macroscopic geometry, is non-surgical and has fewer side effects and limitations than those seen in refractive surgeries. For instance, patients with thin corneas, dry eyes, and other abnormalities cannot undergo refractive surgery. The study, which could lead to treatment for myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, and irregular astigmatism, was published May 14 in Nature Photonics.

“We think our study is the first to use this laser output regimen for noninvasive change of corneal curvature or treatment of other clinical problems,” says Vukelic, who is a lecturer in discipline in the department of mechanical engineering. His method uses a femtosecond oscillator to alter biochemical and biomechanical properties of collagenous tissue without causing cellular damage and tissue disruption. The technique allows for enough power to induce a low-density plasma within the set focal volume but does not convey enough energy to cause damage to the tissue within the treatment region.

“We’ve seen low-density plasma in multi-photo imaging where it’s been considered an undesired side-effect,” Vukelic says. “We were able to transform this side-effect into a viable treatment for enhancing the mechanical properties of collagenous tissues.”

The critical component to Vukelic’s approach is that the induction of low-density plasma causes ionization of water molecules within the cornea. This ionization creates a reactive oxygen species, (a type of unstable molecule that contains oxygen and that easily reacts with other molecules in a cell), which in turn interacts with the collagen fibrils to form chemical bonds, or crosslinks. The selective introduction of these crosslinks induces changes in the mechanical properties of the treated corneal tissue.

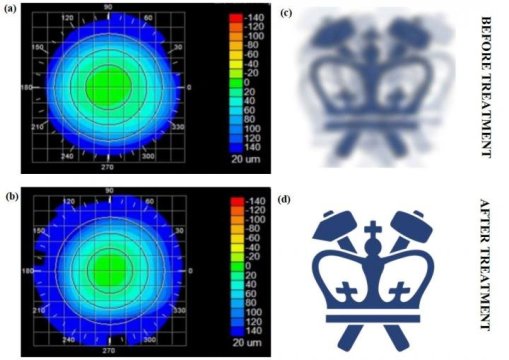

When his technique is applied to corneal tissue, the crosslinking alters the collagen properties in the treated regions, and this ultimately results in changes in the overall macrostructure of the cornea. The treatment ionizes the target molecules within the cornea while avoiding optical breakdown of the corneal tissue. Because the process is photochemical, it does not disrupt tissue and the induced changes remain stable.

“If we carefully tailor these changes, we can adjust the corneal curvature and thus change the refractive power of the eye,” says Vukelic. “This is a fundamental departure from the mainstream ultrafast laser treatment that is currently applied in both research and clinical settings and relies on the optical breakdown of the target materials and subsequent cavitation bubble formation.”

“Refractive surgery has been around for many years, and although it is a mature technology, the field has been searching for a viable, less invasive alternative for a long time,” says Leejee H. Suh, Miranda Wong Tang Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at the Columbia University Medical Center, who was not involved with the study. “Vukelic’s next-generation modality shows great promise. This could be a major advance in treating a much larger global population and address the myopia pandemic.”

Vukelic’s group is currently building a clinical prototype and plans to start clinical trials by the end of the year. He is also looking to develop a way to predict corneal behavior as a function of laser irradiation, how the cornea might deform if a small circle or an ellipse, for example, were treated. If researchers know how the cornea will behave, they will be able to personalize the treatment — they could scan a patient’s cornea and then use Vukelic’s algorithm to make patient-specific changes to improve his/her vision.

“What’s especially exciting is that our technique is not limited to ocular media — it can be used on other collagen-rich tissues,” Vukelic adds. “We’ve also been working with Professor Gerard Ateshian’s lab to treat early osteoarthritis, and the preliminary results are very, very encouraging. We think our non-invasive approach has the potential to open avenues to treat o