What do you do when the most extraordinary investor the world has ever seen delivers merely average results for a decade or more? Especially, when that investor is about to turn 88 years old?

Sadly or not, you begin preparing for a future that looks different than the past.

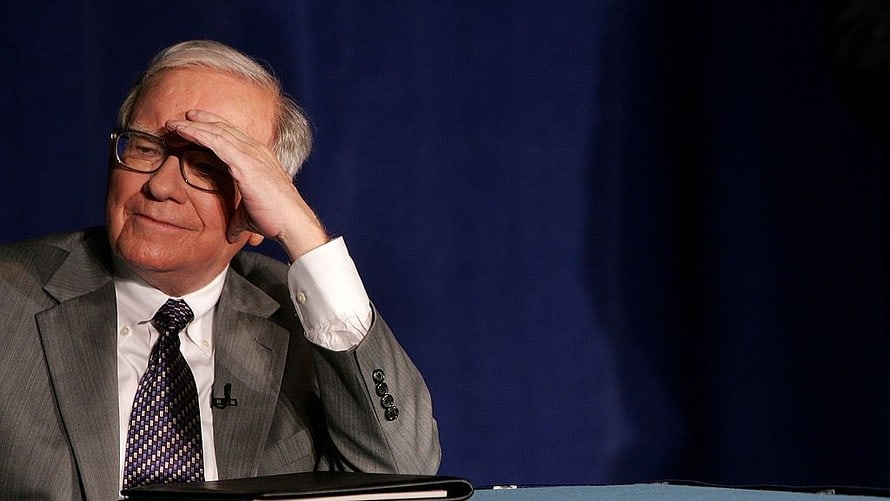

What will happen to Berkshire Hathaway BRK.B, -0.16% when legendary CEO Warren Buffett retires or, as expected, dies while still at the helm of Omaha, Neb.-based Berkshire. Whenever that may be, and hopefully not soon.

Buffett, both a skilled executive and investor, has beaten the S&P 500 Index SPX, +0.22% 155-fold over his 50-plus years running Berkshire, all with a just-folks attitude that couldn’t stand in sharper contrast to folks like Carl Icahn who have made lesser billions while reaching for far more credit.

Underperforming the market

Sad or not, here it is: Berkshire hasn’t beaten the S&P 500 or the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.12% by any of the following periods: One year, three years, five years, nine years (roughly, the recovery from the 2008 crash, which bottomed in March 2009) or 10 years. It hasn’t beaten insurance companies — and insurance is its largest operating business. It’s sitting on more than $100 billion in cash because it finds most available deals overpriced. It’s heavily committed to utilities, which Berkshire runs well, but which are not a great business in the future.

And the investment pool of stock bets on other companies that made Buffett legendary has slipped from world-beatingly great — since 1964, Berkshire’s increase in stock-market value is a stupefying 2.4 million percent — to basically pretty good. It’s really too large to post returns that beat the market by much anymore.

Let’s be real: A conglomerate of unrelated businesses like Berkshire, which owns everything from ultra-sophisticated reinsurance companies to Dairy Queen, hasn’t been considered the optimal way to run corporations since the 1970s. Berkshire was always a special case — the common thread of owning the businesses it operates was that each would generate high and stable earnings that Buffett and Berkshire vice chairman Charlie Munger would invest in stakes in other companies.

Gifted hands

In Buffett’s and Munger’s hands, it was a brilliant strategy, and even when it ceased to be brilliant, thanks to the maturation of long-held investments like Coca-Cola KO, -0.57% and American Express AXP, -0.33% it still did pretty well. But the impact of the law of large numbers is clear.

Berkshire’s sheer size means that if Buffett made another bet as brilliant as his 1988 investment in Coke, it wouldn’t do nearly as much for Berkshire’s returns. That position is now worth more than $18 billion, but it doesn’t drive returns nearly as much as it did when Berkshire stock traded at about one sixtieth of today’s price. (Coke also is trading, after many swings, about where it peaked in 1998.)

Much the same is true of American Express, which Buffett entered by investing when the charge-card giant was struggling under the weight of bad loans to a salad-oil company in 1963 and its shares were radically undervalued. And, as with Coke, Buffett made most of his money decades ago.

More recently, Buffett made post-financial crisis bets that are just as brilliant in companies like Bank of America BAC, +0.21% and Goldman Sachs GS, +0.02% each of which cut him a discount as they sought, basically, to rent Buffett’s well-earned reputation for probity in order to help them recover from the mortgage bust and its aftermath. In Goldman, he made a 64% return within five years and still owns almost $3 billion of shares. Bank of America got $5 billion in capital in a deal where Buffett has quadrupled his money in seven years.

Yet even with those deals, Berkshire’s now so big that it can’t beat the market. Its 40-plus stock portfolio and its operating businesses are too heavy an anchor.

Mistakes were made

Buffett and Munger have also made choices, which one could call mistakes, along the way. Their preference for mature, cash-flow generating businesses that aren’t much exposed to technology risk means they missed most of the tech boom, now 30 years old. Recently, following the lead of Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, its next-generation fund managers, Berkshire has made billions on an Apple AAPL, +1.24% position now worth more than $45 billion. But it didn’t get into Apple until 2016, 32 years after its initial public offering.

There were plenty of consumer-tech businesses that met (very broadly) Berkshire’s criteria, if at prices Buffett didn’t like to pay. Facebook FB, +1.35% and Alphabet GOOG, -0.56% to name two, were profitable long before they went public, and have paid Buffett-like returns since their initial public offerings. They were both better values than IBM IBM, +0.21% one of Buffett’s worst-ever bets, since liquidated. IBM was cheap but not a value stock.

And this is how Berkshire does under two investing demigods. It only gets harder when mortals take over.

The next chapter

Barron’s Andrew Bary recently published a helpful piece about steps Berkshire can take to smooth the post-Buffett transition, and it’s correct if one grants the assumption that Berkshire should stay one company. Berkshire probably should consider a dividend, it might well spin off some businesses, and should soon clarify who will succeed Buffett and let that person begin to impress the market independently of the boss.

But still. The job’s been made so big that even Buffett hasn’t done it well lately. This doesn’t bury Caesar — it praises him, for making his own job undoable. Whoever comes next should make a new Berkshire — more likely than not a lot of little ones.