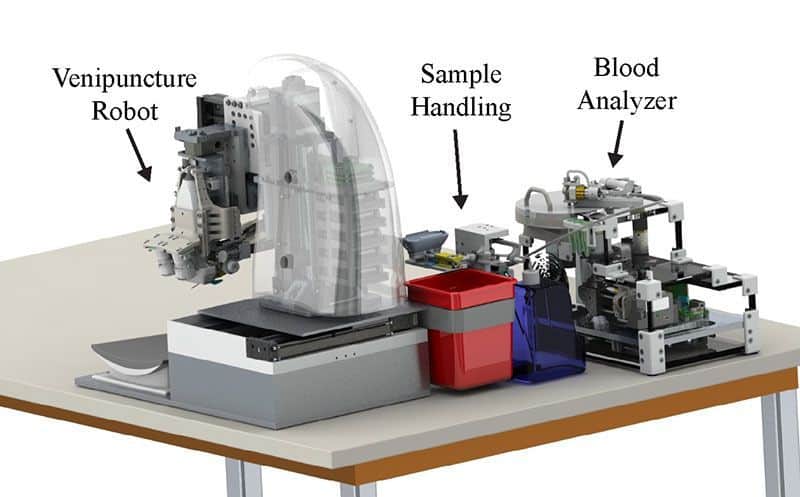

Scientists have developed a “venipuncture robot” that can automatically draw blood and perform lab tests, no humans needed

t’s distressing for the patient and perhaps even more distressing for the parents: your child needs a blood test, but the phlebotomist has trouble locating his tiny veins, and is forced to stick him again and again.

Researchers at Rutgers University say they may have found the solution: a “venipuncture robot.” The robot uses a combination of near-infrared and ultrasound imaging to find blood vessels, then creates a 3D image of the vessels before sticking the patient with a needle. The technology can potentially help make blood draws much quicker and easier, especially in difficult populations: children, the elderly, the obese, and people with dark skin (whose veins are more difficult to see on the surface).

The robot’s creators hope it can make blood draws safer for both patients and healthcare providers. Patients commonly experience bruising from wayward blood draws, and can rarely (less than 1 in 20,000) receive injuries to their arm nerves. Care providers can be accidentally stuck with needles, necessitating stressful testing for diseases like HIV and Hepatitis C. Globally, up to 65 percent of healthcare workers will eventually receive a needlestick injury, though the rates of those who will end up with infections is low (about 3 in 1,000 workers stuck with a needle from an HIV infected patient will contract HIV; with Hepatitis C it’s about 30 in 1,000, and 300 in 1,000 for Hepatitis B).

“There are about two billion blood draws done in the U.S. alone each year,” says Martin L. Yarmush, the bioengineering professor who led the project. “It is the number one patient injury procedure. It’s also the number one clinical injury procedure. The device is meant to take over such that nobody touches a needle.”

The tabletop device is also capable of doing instant blood analyses like white blood cell counts and hemoglobin measurements, which could mean blood samples don’t need to be sent away to a lab. The patient simply places their arm on the device’s platform and waits for the needle stick, then the blood flows directly to a centrifuge-based analyzer. In theory, this could mean that when a nurse comes to take a patient’s weight and blood pressure before a doctor’s appointment, they could also do some simple blood tests, with results ready within minutes, before the patient ever sees a doctor. Yarmush and his team hope portable versions of the device could be useful for EMTs or army medics. It could also be especially valuable in settings where there’s a lack of trained medical personnel, such as refugee clinics.

The idea for the robot has been brewing for some 30 years. Yarmush was a trainee medical doctor working at a hospital when one night he saw some nurses trying to get an IV into a small child.

“It was a nightmare because the child was screeching, the mother was screaming, they couldn’t find the vein,” he says. “It turned out they had to call the pediatric surgeon to do a cutdown to expose the vein. At that point I said to myself ‘there has to be a better way.’”

The idea lay dormant until a decade ago, when Yarmush and his team began exploring how they might automate the process of blood-taking. So far they’ve tested the prototype robot on mock arms, which have tissue-like properties and tubes containing blood-like substances. A study describing the device was was recently published in the journal TECHNOLOGY. They hope to begin clinical trials after this summer.

Pierre Dupont, an expert in bioengineering, including robotic devices, at Boston Children’s Hospital, says the robot is an interesting piece of technology that could be especially useful in settings where there aren’t enough skilled phlebotomists. It’s not the first such device to be developed, he says, but none have made it to market with success yet.

Dupont cautions that there are several challenges in making any new medical device part of routine care. One challenge is integrating the device into medical settings—how big is it? Where does it sit? Do care providers find it awkward to use?

Another challenge is training.

“With high-tech equipment, even if you give it to very experienced personnel, until they’re very experienced with that equipment there’s a chance for a screwup,” Dupont says.

But the biggest challenge is often price. Will the device be cheap enough to make it worthwhile for hospitals and doctors’ offices to buy? That’s hard to predict, Dupont says, as the price of a device tends to go up as it moves through stages of testing and approval.

“Unless you can sell large volumes—and that could be possible in this case—it’s tough to get the price down enough that you could make this a standard of care,” Dupont says. “But if you don’t try, you never find out.”

Yarmush says he and his team designed their device to to consider workflow questions, and to minimize the need for training and the possibility of human error.

“We wanted to create a device that would perform venipuncture procedure with little to no human involvement, thus minimizing human error,” he says. “As such, our automated device requires little to no training, allowing it to be easily adapted to any clinical environment.”

The team has also considered the issue of pricing, Yarmush says. By reducing facility costs and making blood draws quicker, they hope to save hospitals money.

As for whether the device will say “one, two, three…tiny pinch!” or deliver Frozen Band-Aids: children may have to wait for a later model.