It’s the largest hot desert in the world: the Sahara, a blistering landscape of sand, heat, and deadly dryness that swallows 10 nations and is growing bigger all the time.

Because of its searing, sunny conditions, numerous energy projects are already seeking to capitalise on the immense solar potential of the Sahara.

But new research shows an amazing, unprecedented effect of these efforts: solar and wind farms could actually bring rainfall and greenery back to the desert.

“We found that the large-scale installation of solar and wind farms can bring more rainfall and promote vegetation growth in these regions,” says one of the researchers, atmospheric scientist Eugenia Kalnay from the University of Maryland.

“The rainfall increase is a consequence of complex land-atmosphere interactions that occur because solar panels and wind turbines create rougher and darker land surfaces.”

Scientists already knew that wind and solar farms produced localised effects on things like heat and humidity in the regions they’re installed, but nobody knew quite how these effects would play out if you were to build a massive renewable energy complex in the Sahara desert.

The reasons the Sahara is desirable for such a facility are numerous. The desert has a great natural supply of solar and wind energy, it’s sparsely populated, and the landscape isn’t widely used for other things humans need, like agriculture.

Plus, along with the milder, transitional Sahel region to the desert’s south, the Sahara is located close to Europe and the Middle East – which have huge energy demands – and of course to sub-Saharan Africa, whose energy needs are projected to grow in the future.

But if we deployed wind turbines and solar panels across the Sahara and the Sahel, it wouldn’t just be a benefit for renewable energy – first-of-its-kind modelling suggests the environment itself would begin to be transformed by the introduction of turbine blades and solar panels.

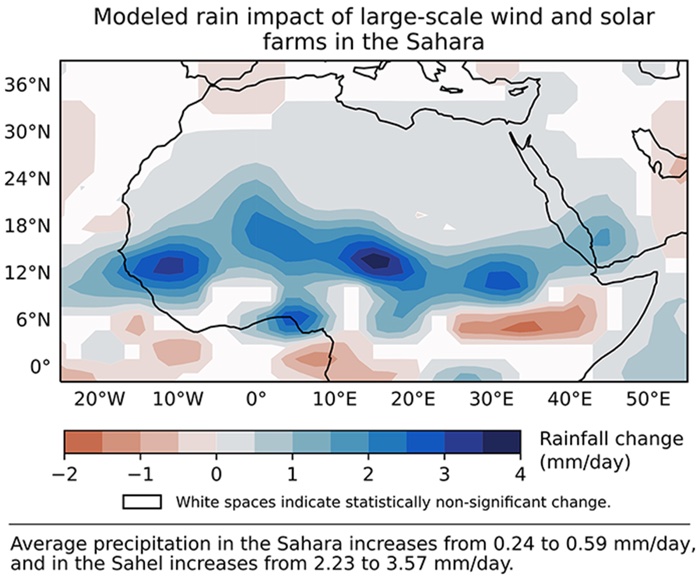

“Our model results show that large-scale solar and wind farms in the Sahara would more than double the precipitation in the Sahara, and the most substantial increase occurs in the Sahel, where the magnitude of rainfall increase is between ~200 and ~500 mm per year,” says first author of the study Yan Li, who began the research at Maryland and is now at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“As a result, vegetation cover fraction increases by about 20 percent.”

These effects arise for a couple of reasons. Firstly, wind turbines enhance vertical mixing of heat in the atmosphere, pushing higher, warmer air down to the surface and increasing land surface friction, and ultimately leading to greater likelihood of precipitation.

“This increase in precipitation, in turn, leads to an increase in vegetation cover, creating a positive feedback loop,” Li explains.

At the same time, solar panels, which soak up the Sun’s rays, reduce what’s called surface albedo – the amount of light reflectance at the surface – which also ends up increasing precipitation.

It wouldn’t be easy to build this kind of hypothetical infrastructure, of course – we’re talking a solar farm roughly the size of China or the United States, punctuated by giant turbines covering about 20 percent of the Sahara.

But if we could pull such an epic feat off, we wouldn’t just be kickstarting a gradual greening of the Sahara desert – we’d also completely kick our addiction to fossil fuels, with the complex delivering about 82 terawatts of electrical power annually, the team calculates.

“In 2017, the global energy demand was only 18 terawatts, so this is obviously much more energy than is currently needed worldwide,” Li says.

Given everything we know about what fossil fuels are doing to the planet, the research offers a little glimpse of how alternative energy technologies could reveal surprising environmental advantages we’re not yet aware of.

“In addition to avoiding anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels and the resulting warming, wind and solar energy could have other unexpected beneficial climate impacts when deployed at a large scale in the Sahara, where conditions are especially favourable for these impacts,” the team writes in their paper.

With the power surplus provided by such a facility, the researchers say you could help realise other difficult, large-scale environmental projects, such as desalination of seawater and transporting it to regions that suffer from freshwater scarcity, in turn bolstering health, food production, and even biodiversity.

Of course, this is all just based upon a simulation for now, and a hypothetical vision that would be difficult to realise in reality. But it’s the right kind of idea to get this planet back on track – a dream worth thinking about after you wake up.

“The Sahara has been expanding for some decades, and solar and wind farms might help stop the expansion of this arid region,” says air quality researcher Russ Dickerson from the University of Maryland, who wasn’t involved with the study.

“This looks like a win-win to me.”