There is a new technology gripping the markets of the future – technology to wear. Wearables, as they are known, are portable systems that contain sensors to collect measurement data from our bodies. Powering these sensors without wires calls for pliable batteries that can adapt to the specific material and deliver the power the system requires. Micro-batteries developed by the Fraunhofer Institute for Reliability and Microintegration IZM provide the technical foundation for this new technology trend.

In medicine, wearables are used to collect data without disturbing patients as they go about their daily business – to record long-term ECGs, for instance. Since the sensors are light, flexible and concealed in clothing, this is a convenient way to monitor a patient’s heartbeat. The technology also has more everyday applications – fitness bands, for instance, that measure joggers’ pulses while out running. There is huge growth potential in the wearables sector, which is expected to reach a market value of 72 billion euros by 2020.

How to power these smart accessories poses a significant technical challenge. There are the technical considerations – durability and energy density – but also material requirements such as weight, flexibility and size, and these must be successfully combined. This is where Fraunhofer IZM comes in: experts at the institute have developed a prototype for a smart wristband that, quite literally, collects data first hand. The silicone band’s technical piece de resistance is its three gleaming green batteries. Boasting a capacity of 300 milliampere hours, these batteries are what supply the wristband with power. They can store energy of 1.1 watt hours and lose less than three percent of their charging capacity per year. With these parameters the new prototype has a much higher capacity than smart bands available at the market so far, enabling it to supply even demanding portable electronics with energy. The available capacity is actually sufficient to empower a conventional smart watch at no runtime loss. With these sorts of stats, the prototype beats established products such as smart watches, in which the battery is only built into the watch casing and not in the strap.

Success through segmentation

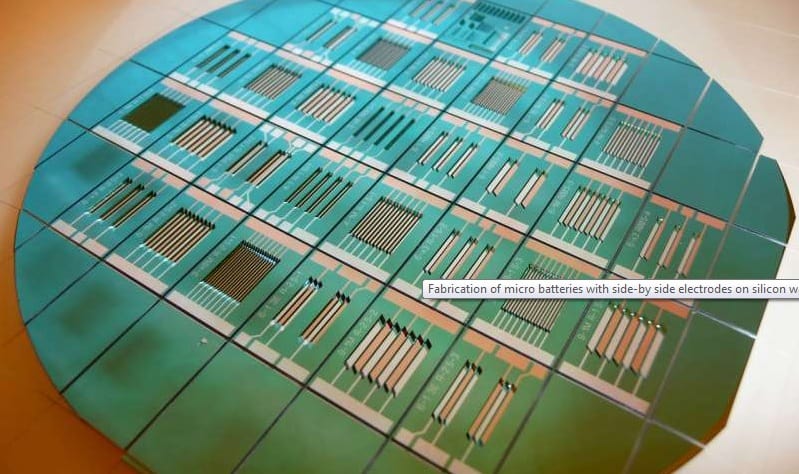

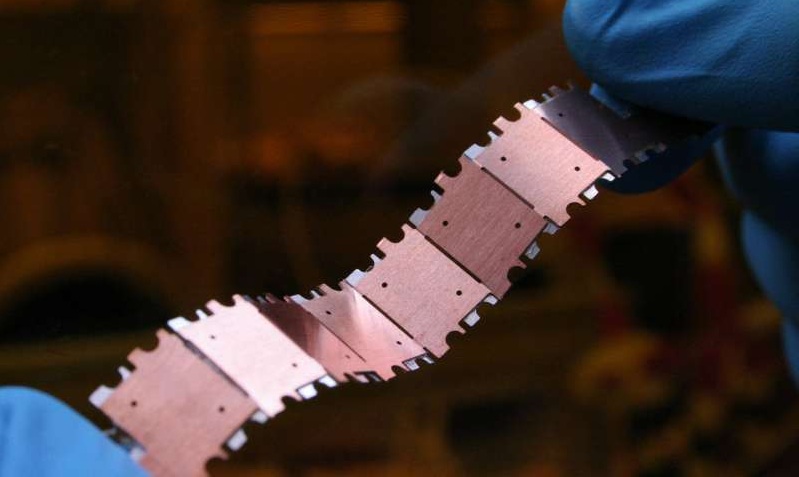

Robert Hahn, a researcher in Fraunhofer IZM’s department for RF & Smart Sensor Systems, explains why segmentation is the recipe for success: “If you make a battery extremely pliable, it will have very poor energy density – so it’s much better to adopt a segmented approach.”

Instead of making the batteries extremely pliable at the cost of energy density and reliability, the institute turned its focus to designing very small and powerful batteries and optimized mounting technology. The batteries are pliable in between segments. In other words, the smart band is flexible while retaining a lot more power than other smart wristbands available on the market.

In its development of batteries for wearables, Fraunhofer IZM combines new approaches and years of experience with a customer-tailored development process: “We work with companies to develop the right battery for them,” explains the graduate electrical engineer. The team consults closely with customers to draw up the energy requirements. They carefully adapt parameters such as shape, size, voltage, capacity and power and combined them to form a power supply concept. The team also carries out customer-specific tests.

Smart plaster to measure sweat

In 2018, the institute began work on a new wearable technology, the smart plaster. Together with Swiss sensor manufacturer Xsensio, this EU-sponsored project aims to develop a plaster that can directly measure and analyze the patient’s sweat. This can then be used to draw conclusions about the patient’s general state of health. In any case, having a convenient, real-time analysis tool is the ideal way to better track and monitor healing processes. Fraunhofer IZM is responsible for developing the design concept and energy supply system for the sweat measurement sensors. The plan is to integrate sensors that are extremely flat, light and flexible. This will require the development of various new concepts. One idea, for instance, would be an encapsulation system made out of aluminum composite foil. The researchers also need to ensure they select materials that are inexpensive and easy to dispose of. After all, a plaster is a disposable product.