Another day, another iconic space mission going dark. On Tuesday, NASA announced that its exoplanet-hunting Kepler Space Telescope had run out of hydrazine fuel, and the craft would be commanded to cease operations. Now, the Dawn spacecraft at the dwarf planet Ceres must face the same fate.

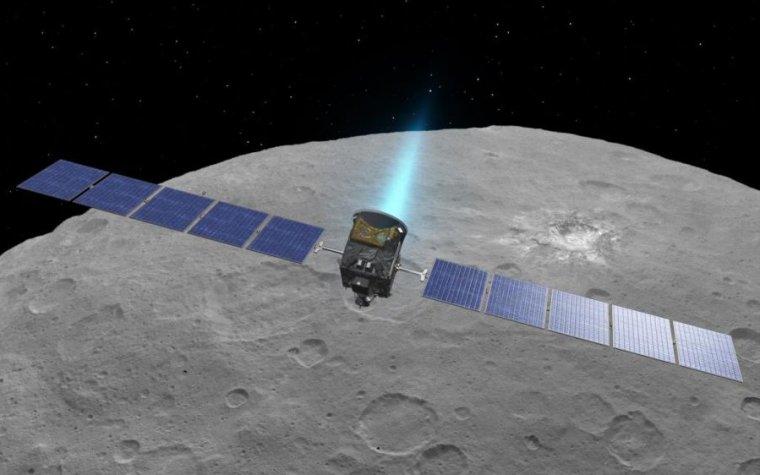

On Wednesday, the spacecraft failed to phone home, and it missed a scheduled connection on Thursday as well. This means that like the Kepler mission, Dawn has run out of hydrazine fuel, which the vehicle needs to orient itself and keep its antennas aligned with Earth. With no fuel, the spacecraft also cannot keep its solar panels turned toward the Sun.

This was not unexpected. Prior to this, because NASA did not want to potentially contaminate the surface of Ceres due to planetary-protection concerns, mission controllers placed Dawn into an orbit around Ceres that will remain stable for decades. It is now a silent sentinel in orbit around the dwarf world it has studied since 2015.

“Today, we celebrate the end of our Dawn mission—its incredible technical achievements, the vital science it gave us, and the entire team who enabled the spacecraft to make these discoveries,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington, in a news release. “The astounding images and data that Dawn collected from Vesta and Ceres are critical to understanding the history and evolution of our Solar System.”

During its 11-year mission, Dawn visited the two largest worlds of the asteroid belt, Vesta and Ceres. Over the course of nearly seven billion kilometers of travel, powered by ion engines, Dawn delivered clues about how the Solar System formed and provided evidence that dwarf planets could have hosted oceans during their history and may still do so today.

At Ceres, scientists found some intriguing mysteries to explore, particularly the many bright spots within the asteroid’s Occator crater. These salt deposits on the surface likely represent the remnants of a frozen ocean with the salt left over from brines as the ocean froze out.

Scientists will continue to mine the data returned by Dawn for years, if not decades, as they seek to determine how planets form and develop, both in our Solar System and beyond.