As revelers on the East Coast celebrate the arrival of a new year, scientists will be crossing another kind of frontier ― 4 billion miles from the sun.

Early on Jan. 1, NASA’s New Horizons probe is scheduled to have a close encounter with the most distant planetary object that humans have ever studied.

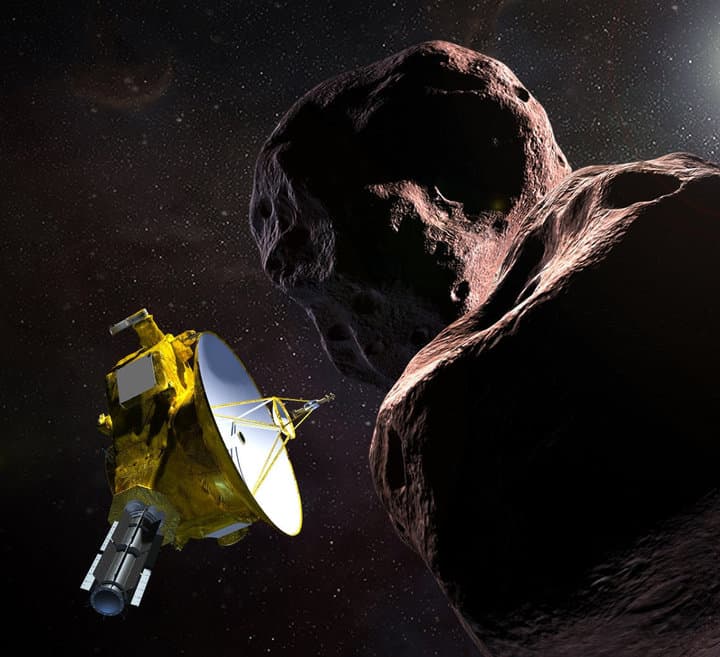

The spacecraft, which zipped by Jupiter in 2007 and Pluto in 2015, is now making its way toward 2014 MU69 ― a mysterious chunk of rock and ice in an almost entirely unexplored region of space.

The object is nicknamed Ultima Thule — “most distant” in Latin combined with the ancient Greeks’ name for the world’s northernmost place. The New Horizons mission team said the nickname refers to “a place beyond the known world.” Ultima Thule is roughly the size of New York City and orbits the sun once every 297 years, according to National Geographic.

But it’s Ultima Thule’s location that makes it interesting to scientists. The object resides 1 billion miles beyond Pluto, in the Kuiper Belt. This region stretches around the sun and is home to millions of icy bodies. Scientists believe these bodies are leftovers from the formation of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago and have remained largely unchanged since then.

“It’s the oldest relic of the solar system we’ve ever studied,” New Horizons team member Marc Buie told National Geographic.

Alan Stern, the NASA mission’s principal investigator, said in a Facebook Live video that scientists aren’t sure what to expect from Ultima Thule. “When we fly past Ultima, we’re going to have a chance to see the way things were back at the beginning,” he said. “It’s completely unknown and unexplored.”

New Horizons launched into space in January 2006. Four years ago, astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope to pinpoint Kuiper Belt objects within the spacecraft’s reach and settled on Ultima Thule.

New Horizons is hurtling through space at 31,500 miles per hour (more than eight miles a second) to reach the object. As it passes Ultima Thule, it will take hundreds of photographs and other measurements to collect more information about the celestial body. The team hopes to map the object’s surface, figure out its temperature and determine if it has an atmosphere, moons or rings.

According to a schedule released by the New Horizons team, the spacecraft will fly by Ultima Thule at 12:33 a.m. Eastern time on Jan. 1. It will travel within 2,200 miles of the body, less than one-third the distance of its closest approach to Pluto.

There’s still some uncertainty, though; New Horizons’ images could come back blurred if Ultima Thule is rotating rapidly, National Geographic reports. And there’s also a chance that the spacecraft’s camera could miss it completely.

“We might get it, and we might not,” Stern said on Facebook Live. “And if we get it, it’s going to be spectacular.”

The New Horizons team will be counting down to the spacecraft’s closest approach to Ultima Thule early on New Year’s Day. Some results from the encounter will be shared in the following days, but it will take the spacecraft until 2020 to send all the data from the encounter back to Earth.

Michael Buckley, the New Horizons team’s media spokesperson, told HuffPost that the partial government shutdown that started Saturday will have no effect on the project’s mission or science operations.

In case the shutdown remains in effect on Jan. 1, the team has partnered with the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory to provide live coverage of the flyby.

Coverage will be streamed on the laboratory’s YouTube channel and the New Horizons mission website.