It turned out to be the little sprout that couldn’t.

The vaunted cotton seeds that on Tuesday China said had defied the odds to sprout on the moon — albeit inside a controlled environment — have died.

China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency announced the news, simply stating: “The experiment has ended.”

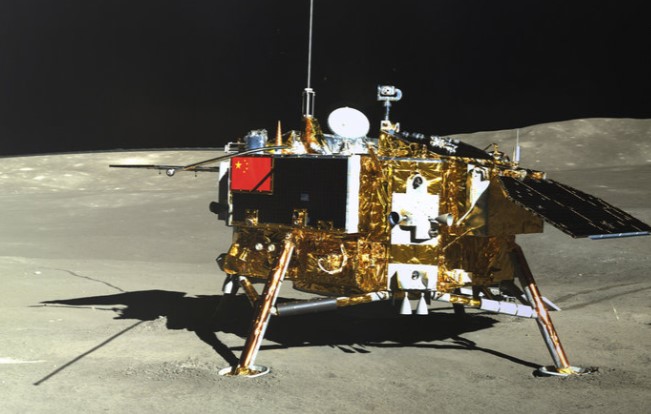

But China’s greater Chang’e-4 mission goes on. Earlier this month, China announced it had become the first country to land a probe on the far side of the moon, in what is largely a scientific mission and is also preparation for sending Chinese astronauts to the moon.

Tucked aboard the spacecraft were seeds within a biosphere equipped with some of the comforts of home: water, soil, air and a heat control system, Chinese researchers said. Once the probe touched down, ground control instructed the probe to water the seeds.

And on Tuesday Chongqing University announced that photographs of tender cotton shoots revealed “the first green leaf growing on the moon in human history was successfully realized.”

A claim, which while perhaps technically correct, may not be precise.

“China has grown the first leaf in a specially designed chamber that was placed on the moon,” Melanie J. Correll, associate professor at the University of Florida’s Agricultural and Biological Engineering Department told NPR in an email. “[The] plants were not exposed to the extreme environments of the moon.”

But still the conditions proved too harsh.

Xie Gengxin of Chongqing University, who designed the experiment, told CNN that the temperature inside the biosphere was bouncing around so much that no life could be sustained and the control team remotely shut down power inside.

In all, Chongqing University said it sent six organisms to the moon, including potato seeds, yeast and fruit flies.

But Xie told CNN that the temperature swings were so extreme they likely killed everything.

The Xinhua news agency quoted China’s National Space Administration as saying, “the organisms will gradually decompose in the totally enclosed canister.”

Despite their reaching an untimely end, Simon Gilroy, Professor of Botany at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told NPR that the seeds are still germinating big hopes.

“If we want to live longer-term off the surface of the Earth, could we take along the biology that we use to keep us alive?” he said. “It’s fantastic to be able to sort of say, yeah, it’s a first tiny step down that path.”

Yet the answer to a key question remains elusive, Gilroy said: “How do you become a good gardener in space?”

“Trying to move the Earth’s environment to the moon is the hardest thing,” Gilroy said. “You need water, light, the temperature has to be right and you have to provide the nutrients you normally get from the soil.”

Correll said as scientists and engineers work on improving the technology needed to grow plants remotely, the plants themselves may also hold the answer. “These types of studies are critical in order to develop new plants designed for these challenging environments and to grow them to support long-term human space exploration,” Correll said.