The bond market looks like it sees a recession on the horizon, while the stock market appears to have plenty to be optimistic about — including a possible trade deal.

But in reality, it’s the Federal Reserve that’s made investors happy to buy both markets, and that’s driven bond market volatility to near record lows and the VIX, the stock market’s volatility index, to a low in the mid teens. On Wednesday, the Fed releases the minutes of the Jan. 30 meeting, the one where it did an about face and indicated it could hold off raising interest rates and stop the unwind of its balance sheet sooner than expected.

The so-called ‘Powell pivot’ has brought a relative lull to markets after the wildness of late 2018, where the stock market plummeted and bond yields dipped amid fears of both recession and that the Fed was raising interest rates too much. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, in a briefing after that meeting, stressed the Fed would be ‘patient’ and flexible.

“It almost seems like we’re back in a bit of a QE period, where the S&P keeps ripping and rates are flat. I think a lot of this has to do with Fed guidance,” said Mark Cabana, head of short rate strategy at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. QE, or quantitative easing, was the financial crisis era asset purchase program the Fed embarked on to add liquidity to markets and help the economy. It is now in the process of shrinking its balance sheet, by replacing fewer securities as they mature.

“If you look at the January FOMC on Jan. 30, since that point in time, rates are lower by around 10 basis points (on the 10-year) and the stock market is up 5 percent,” said Cabana. Because it had such a profound impact on markets, market pros are now watching closely to see if the Fed gives more details on its balance sheet or explains why it suddenly switched to a policy of holding back on rate hikes for now.

“The big questions they have to answer are whats the minimum quantity of reserves they’d like to have in the system? What are their thoughts on tapering. Is it useful?…What’s the composition of the Fed balance sheet assets they would ideally like in the long run?” said Cabana.

The 10-year yield fell Tuesday, trading as low as 2.63 percent.

“I think that’s a function of the market continuing to be worried about the economic outlook and looking to a potential recession. We’re heading to the lower end of the yield range. The market has been in ‘buy the dip’ mode ever since the Fed changed its tune,” said John Briggs, head of strategy at NatWest Markets. “Part of it is the grind lower in European yields, the economic news continues to be poor and part of it is looking ahead to the FOMC minutes..”

U.S. yields often follow the German bund yields, which have moved lower on weaker European data and political uncertainty in Europe. The German 10-year bund yield was 0.10 percent Tuesday, whilel the U.S. 10-year has been in a recent range of 2.60 to 2.80 percent.

“You’ve gone from a Fed on the move to a Fed on hold,” Briggs said. “The global growth outlook has gotten worse and global central banks have turned more dovish. The winds are shifting in that direction rather than the other way…Nobody’s moving like people thought they would six to eight months ago.”

The fact that both stock and bond prices are rising is not the usual state of things. While it can happen, traders take it to mean that one market is getting it wrong. For instance, the bond market may prove to be overly gloomy for pricing in the potential for a future recession, or the stock market may turn out to be just too exuberant as it moved higher with no regard for a slowing global economy or weaker earnings. Bond yields move opposite price, so as stocks have risen, yields — or interest rates — have been coming down.

“One way to interpret the moves is an extremely dovish Fed is going to keep interest rates low, and let risk rise. The Fed’s goal at this point is to extend the expansion,” said BMO senior rate strategist Jon Hill. “If they’re able to do so, that means lower rates, higher equities. If they’re not able to do it we’re looking at the end of the cycle and looking back at zero rates,’ he said. “The Fed would start cutting rates, possibly as far as returning to zero percent.”

Hill said the mystery is the dollar and why it continues to rise as yields slide. One explanation is that the dollar is trading higher on the fact the U.S. economy is still relatively strong compared to other parts of the world.

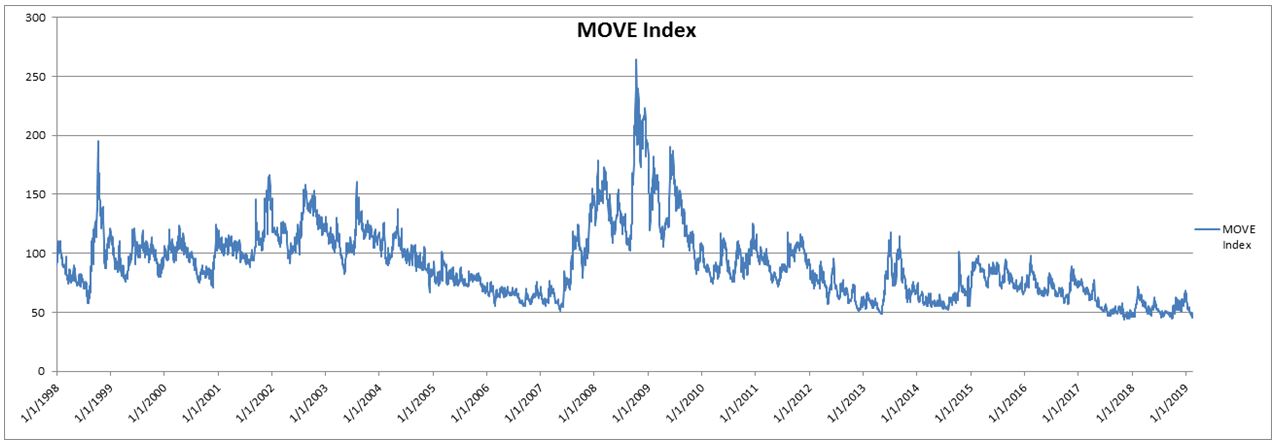

The fact that the bond market has become far less volatile is apparent in the Merrill Lynch MOVE index. It has returned to a near historic level it has been at 2017 and again in 2018, but also during the financial crisis. The index is based on options on Treasurys.

“The volatility, in terms of implied volatility is quite low. We think that has to do with uncertainty being high and the Fed being very soothing. The Fed being soothing takes out the risk that they would look to move any time soon. That depresses vol,” said Cabana. He said the market is also wary of Brexit, the U.S.-China trade talks and political discontent in Europe, among other things.

“It reduces market participant’s willingness to have firm macro views…The uncertainty is weighing on market participants’ and business. How are you going to decide to make a big R and D and cap ex expenditures when you’re worried a key par to your supply chain could be subject to a 25 percent cost increase. That uncertainty coupled with a dovish Fed is contributing to low levels of volatility,” said Cabana.

Strategists say the Fed could return to raising interest rates, if a trade deal is struck between the U.S. and China and the economic data improves.

MOVE Index (Treasury volatility)