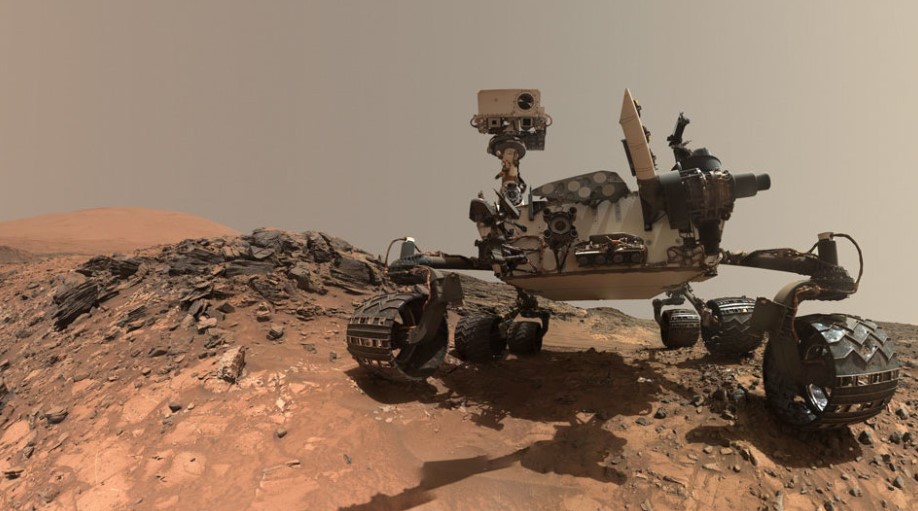

NASA’s Curiosity rover shook the science community six years ago when it apparently detected traces of methane—an important chemical linked to life—on Mars. Researchers failed to confirm these results in the years that followed, but that’s now changed thanks to a re-analysis of data collected from orbit.

New research published today in Nature Geoscience confirms that NASA’s Curiosity rover detected a methane spike on June 15, 2013, while exploring Gale Crater on Mars. The new paper, led by Marco Giuranna from the Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology in Rome, Italy, doesn’t explain how methane came to exist on the Red Planet, but the independent confirmation is a potential sign that Mars once featured conditions suitable for life during its ancient past. More radically, it suggests microbial life once existed on Mars, producing the smelly gas that’s now escaping from the planet’s bowels.

That methane might exist on Mars is an issue of considerable debate. Methane is a key requirement of habitability, and possibly even a signature of life itself. The trouble with methane, however, is that it doesn’t last long in the atmosphere. Any methane that is detected would therefore have been released relatively recently. For Mars, this means the gas is likely venting up from beneath the surface. What’s more, the sporadic, intermittent nature of these apparent methane spikes suggests the methane is being released at irregular intervals.

Proving that methane exists on Mars would be a huge deal, so scientists have been extra careful to avoid any missteps in this area. The Curiosity detection from 2013 was intriguing, but because the observation could not be corroborated by other instruments, such as in-orbit satellites, it could not be definitively confirmed.

Confirmation of the Curiosity measurement has now happened owing to a re-analysis of data collected by the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter at the time. Specifically, data collected by the spacecraft’s Planetary Fourier Spectrometer on June 16, 2013, when it was above Gale Crater, are in accordance with measurements taken by Curiosity the day before. It’s the first time that measurements made on the ground have been confirmed by a spacecraft in orbit, according to an ESA statement.

Giuranna and his colleagues confirmed the Curiosity observation by looking at 20 months of data collected by Mars Express, and also by developing a new technique that allowed the researchers to scour through hundreds of measurements made over a single area. Interestingly, Mars Express detected no other methane spikes during the observational period aside from the one detected by Curiosity.

“In general we did not detect any methane, aside from one definite detection of about 15 parts per billion by volume of methane in the atmosphere, which turned out to be a day after Curiosity reported a spike of about six parts per billion,” said Giuranna in a statement “Although parts per billion in general means a relatively small amount, it is quite remarkable for Mars—our measurement corresponds to an average of about 46 tonnes of methane that was present in the area of 49,000 square kilometres observed from our orbit.”

At the time of the Curiosity observation, scientists figured the methane originated north of the rover and was carried to the Gale Crater by southerly winds. The new interpretation presented in the new study offers a different scenario. The quantity of methane detected, along with the geology of the area, suggests the methane spike occurred within Gale Crater itself. Two independent analyses were used to reach this conclusion, including computer simulations that assessed the probability of methane emissions from the Martian surface, and the identification of geological features within Gale Crater consistent with the associated methane spike.

This kind of thing happens on Earth, typically along tectonic faults and at natural gas deposits. Something similar may be happening on Mars, in this case, along the faults of the Aeolis Mensae region.

“We identified tectonic faults that might extend below a region proposed to contain shallow ice,” study co-author Giuseppe Etiope from the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology said in the ESA statement. “Remarkably, we saw that the atmospheric simulation and geological assessment, performed independently of each other, suggested the same region of provenance of the methane.”

The researchers theorize that the methane detected on Mars is being caused by small, transitory geological events, rather than a process in which the gas is constantly being replenished in the Martian atmosphere. There’s still much to learn about this process, however, such as how the gas is being removed from the atmosphere, and the nature of the Aeolis Mensae site.