The countdown has begun. It’s T-minus a month or so until the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 — and humanity’s first and famous steps on another world.

In appreciation of that achievement, and the five-decade milestone, a flotilla of books has also been launched exploring Apollo’s story and raising questions about its ultimate legacy. Surveying just a few of these works, it quickly becomes apparent how singular America’s achievement was with Apollo. Even more pressing, however, is how these books show that — half a century later — we’re still grappling to understand its long-term meaning for our nation and the world.

If you’re looking for a good telling of the manned space program’s story, you should start with James Donovan’s Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race And The Extraordinary Voyage Of Apollo 11. Beginning with the American panic after the Russian launch of Sputnik in 1957, Donovan ably maps out the United States’ path to Apollo 11. Once President John F. Kennedy declared, in 1961, that America would reach the moon before the decade was out, NASA found itself on the hook for inventing space-travel on the fly (literally).

Donovan walks the reader though the line of Mercury, Gemini and Apollo missions, each more dangerous and audacious than the last. Donovan knows how to tell a gripping story. With each launch, or failure, NASA’s engineers, managers and astronauts pushed the grand experiment that was human spaceflight a little further. They first had to learn how human beings would even respond to space. Then came learning how to rendezvous and dock two ships in orbit. The next lessons were how to leave Earth’s orbit, sail around moon, and return to safety.

With each step, Donovan gives us choice stories about people on the frontier, like how astronaut Buzz Aldrin campaigned to be the one taking those famous first steps. NASA, though, favored the symbolism of an astronaut not in the military making that giant leap for mankind. So, says Donovan, it was Neil Armstrong, a civilian test pilot, who got the nod. To his credit Aldrin, who Donovan describes as “a loner who was participating in a team sport,” accepted the decision with grace.

If you are interested, though, in how the U.S. launched itself on the improbable mission of getting people to the moon when it could barely get a rocket off the pad, then Douglas Brinkley’s American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy And The Great Space Race may be the read for you. The book’s subtitle reveals all you need to know about its focus. Part Kennedy biography, part political space history, Brinkley’s book makes it clear that launching the Apollo program was all about beating the Russians. As the Brinkley book demonstrates, the president who had the greatest impact on space exploration was, in his own admission, “not that into space.” What American Moonshot shows, however, is that Kennedy was a daring and astute politician who understood that setting Apollo in motion meant leap-frogging over the Russian’s considerable capabilities in space circa 1961. By setting the moon as America’s goal, Kennedy threw down a gauntlet whose consequences would blossom far beyond its Cold War political origins.

Understanding those consequences and setting their story in context falls to Charles Fishman via One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us To The Moon. While Fishman is interested in the origins of the space race and the mechanics of problem solving that got us there, he’s just as concerned with the ways Apollo transformed us. The race to the moon was, in his words, “the largest civilian project ever undertaken, dwarfing not just the Manhattan Project, but the Panama Canal and the transcontinental railroad.” In this way, Fishman wants us to see Apollo as part of a social revolution just as profound as any of the others occurring in the 1960s.

For starters, the scale of what NASA needed to, and did, accomplish in the technologies of management represented its own kind of revolution. Fishman documents how in the dawning years of the 1960s, when Russia was first to get satellites and humans into orbit, it was not entirely clear that democracies had the capacity to marshal the single-minded focus needed to develop a space program. But by 1968, NASA could be counted as “the #4 organization in the country in terms of employees, ahead of every company except for GM, Ford and GE,” Fishman notes. To work so successfully at that scale and at the sharpest and most unforgiving edge of technology was a revolution of its own kind that validated the American forms of democracy and capitalism.

For Fishman, however, the most important and least understood success of Apollo lay in the domain of the digital. One Giant Leap spends considerable and well-used time demonstrating NASA’s role in birthing digital technologies that are now ubiquitous. When the race to the moon began, “integrated circuits” — meaning computer chips — were an uncertain technology. But NASA saw that they would be essential to their need for “real time” computing where answers from machines had to follow just seconds after questions were posed. As Fishman shows, it was NASA that drove this technology, buying 60 percent of all integrated circuits made 1963. More importantly, NASA’s stringent requirements drove the chips to 100-percent reliability — meaning they could fly lunar landers and, eventually, carry out calculations that make the GPS on your phone so accurate.

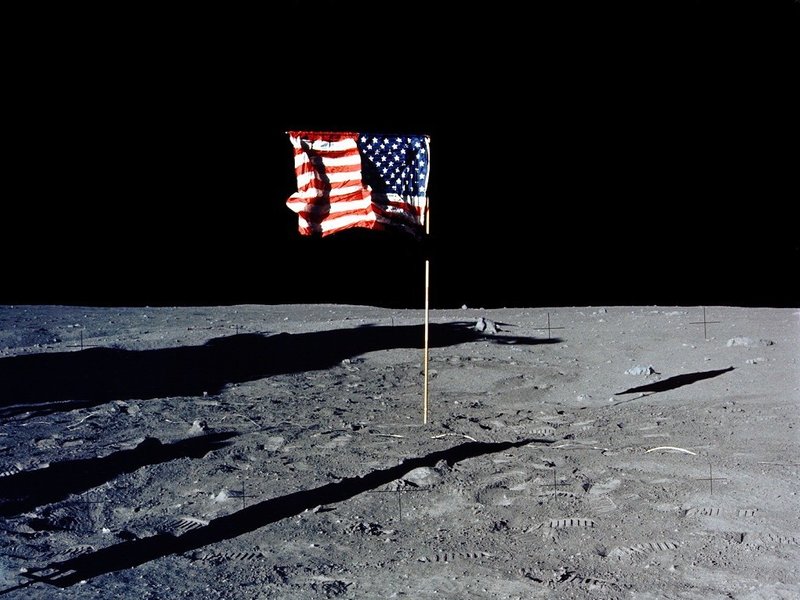

Fishman ends his book with an extended mediation on what this civilian project, carried out in the full light of public transparency (Russia showed nothing of its launches until they were over), meant for the world. He concludes it was important that the U.S. made it to the moon — and not the totalitarian system represented by the USSR — quoting Neil deGrasse Tyson: “No other act of human exploration ever laid a plaque saying ‘We come in peace for all mankind’.”

With its vision, its reach, and its delivery of a new relationship between people and technology, Apollo transformed the world. As Fishman emphasizes, in every way Apollo was both “victory and success.” It’s a lesson we would all do well to remember half a century later.