Often it’s the smallest charge that triggers the biggest fee.

Overdraft fees, which is what banks charge when transactions including debit card purchases cause your account to drop below zero, average $35 — nearly twice the size of the average $20 debit card transaction, according to the Center for Responsible Lending.

Altogether, customers of larger banks paid more than $11 billion for bounced checks and other overdrafts in 2017, according to the most recent data from the Center for Responsible Lending. That does not include the fees collected by small community banks or credit unions, which are not required to report their fee volume to the FDIC.

For some banks, overdraft revenues are a significant part of their income, despite the Federal Reserve’s 2010 regulations that sought to bar them from assessing these fees unless customers have opted into an overdraft protection program.

Now, nine years later, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has opened a review of the “overdraft rule.”

The purpose is to minimize any significant economic impact of the rules on small businesses in particular, the consumer watchdog agency said. From there, the CFPB will determine whether the rule should be continued without change, amended or rescinded.

An overdraft only occurs when consumers lack the funds in their account to cover a transaction, but the bank or credit union pays anyway. Consumers who do not opt in to overdraft coverage will generally have debit card purchases and ATM withdrawals declined with no charge if their account doesn’t have enough funds to cover a transaction.

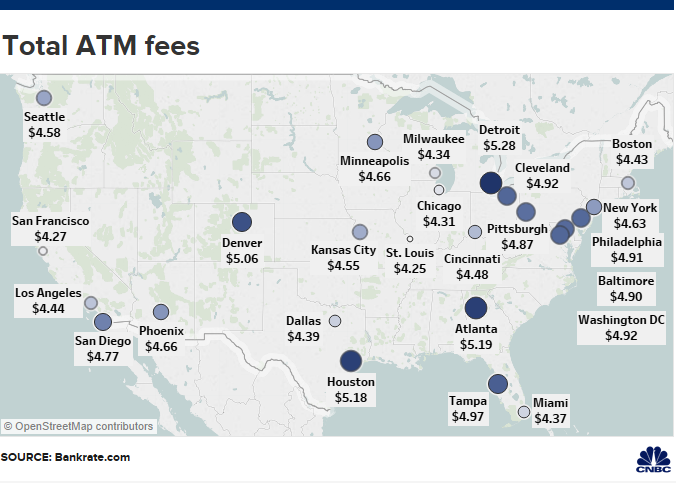

While the average overdraft fee dipped slightly last year, it’s the second-highest that it’s ever been, according to Bankrate.com. (Meanwhile, the average ATM surcharge for using a bank that isn’t your own a hit a record high for the 14th year in a row, see the chart below.)

Although almost half of Americans who’ve had a checking account have been charged an overdraft fee at some point, an earlier study by the CFPB found that a small portion of those who opt in pay substantially more than everyone else.

In fact, 9% of accounts are frequent overdrafters — meaning that they overdraw their accounts more than 10 times a year — and incur 79% of overdraft fees.

Those frequent overdrafters are also the most “financially vulnerable,” the CFPB said, with lower daily balances and lower credit scores.

Overdraft coverage sounds like a good deal, but it’s usually better to steer clear, experts say.

“Avoiding overdrafts is the financial equivalent of being able to walk and chew gum,” said Greg McBride, Bankrate’s chief financial analyst. “Most consumers have it figured out.”

Still, others choose to opt in to overdraft protection because it’s the lesser of two evils — paying the fee is preferable to missing a mortgage payment or a utility bill.

A better option is to link a savings account to your checking account, McBride said. “That way if you do slip up, it’s your money that covers the shortfall.”

“It may cost a nominal fee but it’s better than $35,” he added.