LONG BEFORE TWO COUNTRIES RACED to space and NASA began sending rovers to Mars, curiosity about the skies kept people up at night. For centuries, astronomers (and astrologers) chased knowledge about celestial bodies and their impact on Earth—and turned to cartography to map their findings for the public.

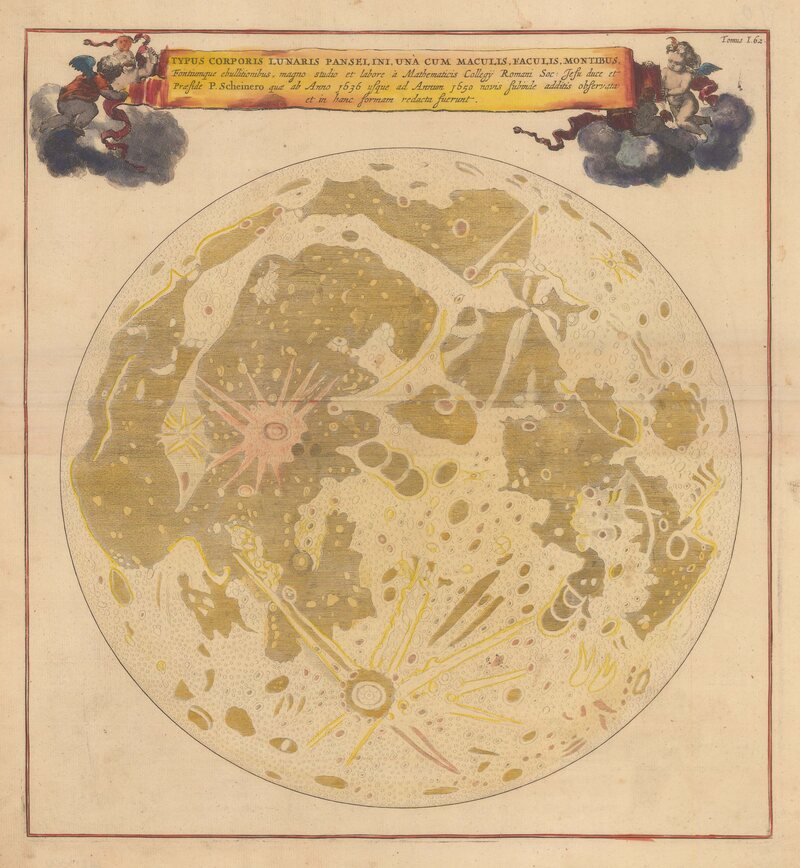

Athanasius Kircher, a German Jesuit priest and scholar, drew a map of the near side of the moon back in the 17th century—300 years before American astronauts would land there. Now a new exhibit called The Mapping of the Moon: 1669-1969, on display through August 21 at The Map House in London, explores the history of lunar and celestial cartography, showing how these renderings brought far-off heavenly bodies into our orbit. The exhibit also documents how scientific knowledge improved over time—but also how the artistry of maps was lost a bit in the process.

“The publication of these early maps coincided with a transformative moment in human history and some of the most important discoveries in astronomy,” say Mary Alice Beal and Charles Roberts of The Map House, who curated this cartographic history of the skies.

Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus’ novel theory—that the solar system was, in fact, heliocentric and did not revolve around Earth (and man)—was aided by these diagrams. And when telescopes were developed as an optical tool in the 17th century, Renaissance astronomers were able to make out stunning details—the Moon’s craters, Saturn’s rings, Jupiter’s moons—which allowed for the creation of maps that depicted not only planets and natural satellites, like the moon, but also the solar system as a whole.

The earliest space race, then, was about which country could build the most impressive observatory first. Royal patrons threw money behind celebrity astronomers, eager to fund exploration of the moon. Astronomers, for their part, were eager to prove their scientific prowess by drawing the most accurate maps. The Map House, the world’s oldest and largest antiquarian map dealer, has scores of these, from the Renaissance to the Cold War.

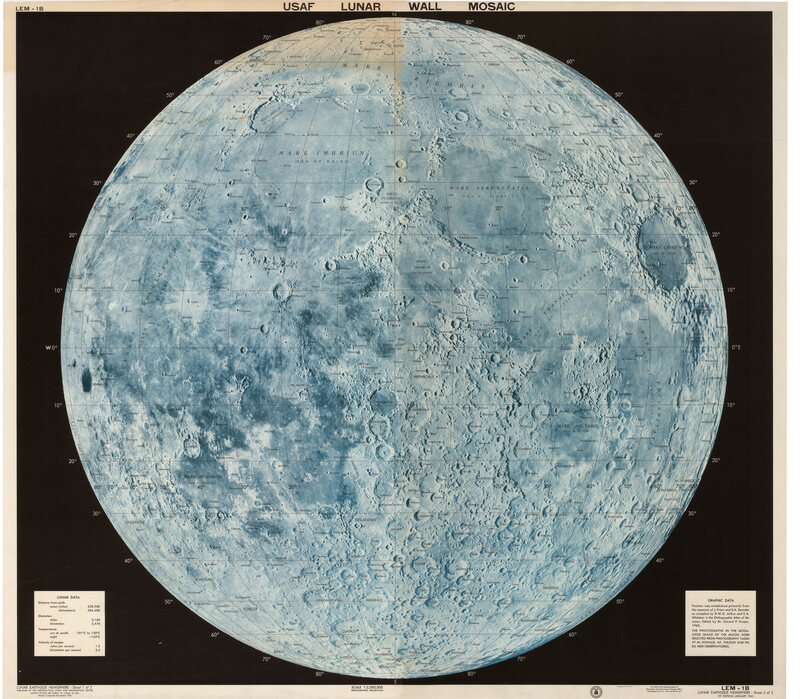

“We are very lucky that we have always had a fascinating selection of antique and vintage maps of the moon, stars, and what was known of the universe,” Beal and Roberts say. “The exhibition features copper-engraved maps published in late 17th-century Europe, and maps … of the Apollo program, [drawn] by the United States Geological Survey and the U. S. Air Force’s Aeronautical Chart and Information Center (ACIC), and … published by NASA.”

In fact, The Map House’s entire collection of cartography, illustrating early astronomical curiosity and subsequent lunar exploration, is for sale. Highlights from this treasure trove include maps of space signed by astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin at the height of their NASA careers.

“With the upcoming anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing and our wish to celebrate this magnificent achievement,” the exhibitors say, “we have been gathering more lunar material over the last few years to really piece together a graphic timeline of how the moon was mapped.”

Along with maps of the moon and the larger solar system, the exhibit boasts “rare lunar globes produced specially to celebrate the Moon landing in July 1969, an extraordinary 1872 solar system model by Henry Bryant, and a very curious French horoscope predictor [circa 1930],” Beal and Roberts say. It also contains 17th-century star charts, lightboxes, and globes, along with a 19th-century brass model of the solar system and boldly designed educational charts used to illuminate constellations, eclipses, tides, and moon phases.

Here, we see the premium that cartographers placed on these historic maps’ aesthetic qualities, beyond their scientific import.

“Many of these early maps were astonishingly beautiful, partially because art and science were not considered separate fields in the 17th and 18th centuries, but rather two sides of the same coin,” say Beal and Roberts.

Andreas Cellarius’s 1660 Harmonia Macrocosmica map illustrates this. “Cellarius’s 29 maps of the heavens are some of the most decorative maps ever published,” the exhibitors say, “especially when they were embellished with glorious hand coloring and gold leaf. Maps and atlases were seen as status symbols by 17th century Europeans—not just because they were expensive to purchase but also because they marked the owner as a worldly individual with an interest in science.”

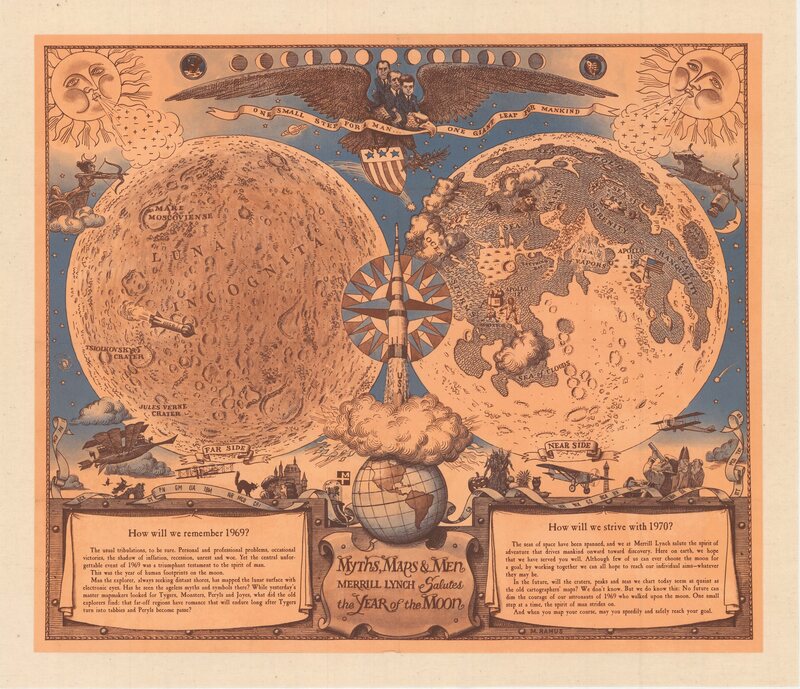

When the U.S.-Soviet race to the moon began in the late 1950s, American organizations started using celestial maps as advertising and propaganda. That led to highly artistic renderings of space. Merrill Lynch, for instance, commissioned a colorful, detailed map of the moon to celebrate the auspicious landing in 1969, complete with Armstrong’s iconic quote across the top. NASA’s U.S. Air Force Lunar Wall Mosaic, an ambitious photo collage showing 281 angles of the moon, is likewise on view at The Map House exhibit.

Alone, each of these maps is impressive. In concert with one another, they allow for a closer look at the moon’s surface—and the heavens as a whole.