When Sheri Reid Grant inherited millions of dollars from her parents, she went into a downward spiral. Six years later, she still gets teary talking about it.

“Everybody thinks money is the answer, and here I had all this money, and all I could think about was not getting it right,” she said.

Grant, 53, was a middle-school teacher in Michigan when she inherited the money.

Paralyzed with fear, she became convinced that any move she made would not only destroy her father’s legacy but ruin her children’s and grandchildren’s future. She suffered through stomach pains, couldn’t get herself out of bed and lost interest in daily activities. The money weighed on her every thought.

Help finally came, not from a financial adviser or a psychologist, but a combination of the two: a financial therapist. The treatment helped her uncover the root of her turmoil: Her father had raised her to believe she didn’t know how to handle money, so the inheritance felt like a trap, something she would never be able to manage.

“If I didn’t have a financial therapist to help me manage the inner chaos and stress, I would have imploded,” Grant said.

And though her circumstances are unusual — few Americans attain her wealth — Grant believes financial therapy can help anyone. Because it isn’t just about how much you have; it’s about your beliefs and feelings toward money. And, boy, do we have a lot of them. Money is, after all, the thing that stresses out Americans more than anything else, according to a 2018 survey — as it has been every year since the American Psychological Association started posing the question in 2007.

In Grant’s case, financial therapy helped her overcome her paralysis and escape self-defeating behaviors such as refusing to look at credit-card statements or avoiding asking her bookkeeper to pay bills.

“Financial therapy helps me with the emotional and the behavioral side of making decisions around money,” she said.

What is financial therapy?

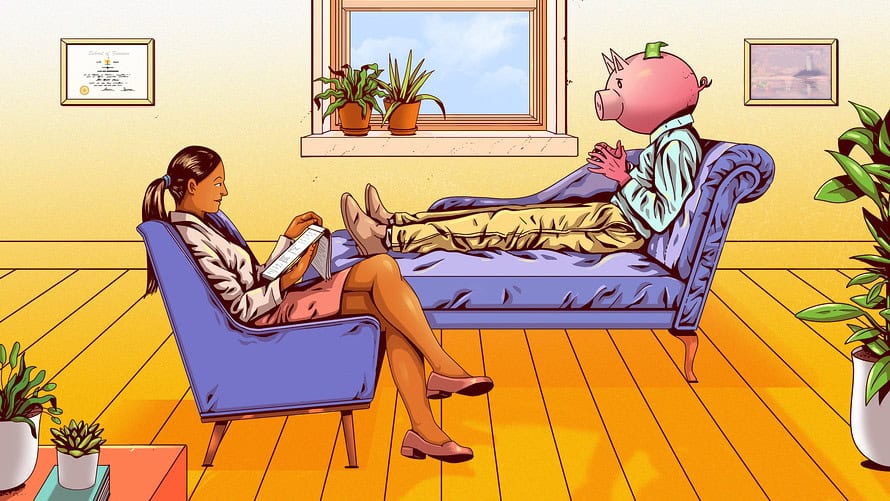

Financial therapy sits at the intersection of financial advice and psychoanalysis. It’s therapy that helps people uncover the source of emotions guiding their money decisions and, in the process, end self-destructive behaviors related to money.

“A person can benefit from financial therapy when their behaviors are not in line with their values,” said Rick Kahler, a Rapid City, S.D.–based financial adviser whose firm, Kahler Financial Group, has employed for the past eight years a financial therapist who is both a certified financial planner (CFP) and a clinical mental-health counselor. “Another way to say that is when someone is stuck or when someone knows I should be doing this — I should be saving, I should be spending less, I should be paying attention to my retirement — but it doesn’t happen.”

Kahler considers a team that includes both therapists and financial planners to be the gold standard for financial-advisory services.

Certifiable

Though it’s been around in various forms since the 1990s, financial therapy is now poised to become more standardized and more prevalent. Until now, the occupation has been loosely defined, and anyone could call themselves a financial therapist.

The field encompasses a range of professionals — from psychotherapists to marriage counselors to social workers to certified financial planners — all looking to help clients understand the emotional underpinnings of their behaviors around money. Starting this year, practitioners will be able to be certified by the Princeton Junction, N.J.–based Financial Therapy Association as a financial therapist after taking a 100-question exam and meeting requirements including logging 500 hours of experience.

Demand for financial therapy is poised to grow, said Debra Kaplan, a Tucson, Ariz.–based licensed mental-health therapist, speaker and author of “For Love and Money: Exploring Sexual & Financial Betrayal in Relationships.” Kaplan has an MBA and first got interested in the psychology of money while working as a commodity options trader on Wall Street. This past decade of stock-market prosperity has coincided with the rise of a generation that is open to self-reflection, she’s observed.

“This is a generation that is introspective by nature because of wanting a work trajectory that is self-gratifying and satisfying, not just a paycheck,” Kaplan said. “Therefore, financial therapy is perhaps coming into its own at a time that has a demographic that would benefit from what it has to offer: delving into money and work and what it means.”

And as traditional financial planning becomes increasingly automated, with investors relying on robo-advisers and index funds, and talk of artificial intelligence helping clients make asset allocations, Kahler sees a bright future for financial therapy.

“The financial-planning profession gives lip service to the fact that it’s about the relationship,” he said. “I don’t think emotional issues are going away. To be relevant, the financial-planning profession needs to embrace financial therapy.”

The case for financial therapy

After nearly 40 years in the financial-advisory business, Kahler, 64, has come to the conclusion that only about 20% of financial-planning clients respond to logic and education. That small minority will, for example, stop overspending if an adviser tells them to. But, for most people, “it goes way deeper,” he said, and they need more than monthly budgets to change their behavior.

Kahler sees a parallel with dieting. We’re bombarded with information about calorie counts and daily walking steps to stay fit, but most Americans are still overweight. “It’s not about the money,” Kahler said. “The money is a symptom of a deeper problem. Until we get down to that emotional issue, the behavior isn’t going to change. You’re just putting a Band-Aid on it.”

Traditional financial planning is not equipped to address that reality. In fact, financial planners call clients who don’t do what they’re told “noncompliant,” Kahler noted.

A financial therapist, on the other hand, will help someone uncover why they can’t seem to get around to opening those 401(k) statements; why they continually overspend on their credit card, even when they’ve promised themselves they wouldn’t do it again; why they have plenty of money and yet won’t spend any of it to repair their dilapidated house or car; why every fight with their spouse seems to be about the household budget; why they’re losing sleep about money and can’t seem to focus; or why they have a secret bank account they’ve never told their spouse about.

How it works

Tackling people’s issues around money with a financial therapist is different in every case, but it often involves examining a client’s core beliefs about money and how they came to hold them. Do they chase money? Are they terrified of running out of money? Is their sense of self-worth tied up in how many figures are in their salary? Do they avoid thinking and talking about money at all costs? Do they think money is irrelevant? Often the discussion will lead back to childhood, when our parents taught us, either consciously or unconsciously, what and how to think about money.

Those “stories” about money are sometimes called “money scripts,” a term coined by Brad and Ted Klontz, a father-and-son team of financial psychologists. Ted Klontz is Sheri Reid Grant’s financial therapist. One of her money scripts — that women don’t know how to manage money — was reinforced every Christmas when she was growing up in Michigan. Her father, an industrial engineer by training, made his fortune after buying a manufacturing company outside Detroit that made automotive parts. Her three brothers worked for the business, but Grant didn’t. At Christmas, the family would gather to open presents, an event that culminated with her dad opening a box of envelopes and handing out distribution checks to her brothers.

The message — that she didn’t know how to handle money — later fueled her “money avoidance,” which manifested in Grant refusing to look at, for example, credit-card statements. Money scripts may seem irrational to an outsider, but for the person living them they are completely logical. Identifying them helps clients recognize the roots of their money-related anxieties, and eventually, it’s hoped, end their harmful financial behaviors.

There’s no exact formula for helping a client change behavior; financial therapy is more art than science, Kaplan said. But as the saying goes, “If you can name it, you can tame it,” so Kaplan will sometimes have clients make an inventory, in writing, of exactly what they feel when they take money-related actions that they want to change.

A client who was going into debt to lend his friends money because he felt it was his duty to rescue them might write down that when he gives a specific friend money, he feels he’s a good friend; when he doesn’t, he feels sad and guilty. In therapy, that client may come to realize his lending habit is more about his own self-esteem, and Kaplan would help him find healthier ways to foster self-esteem. “I’m not going to reprimand them, but I want them to notice what comes up when they engage in that behavior,” Kaplan said.

‘They thought we were a cult’

The origins of financial therapy date to the mid-1990s, when a leaderless group of financial planners — they came from across the country and first met as a group in Colorado — called the Nazrudin Project began gathering once a year to discuss the intersection of emotions and money. The rest of the financial-planning field balked. “They thought we were a cult,” Kahler remembers. “Planners just did not feel that the financial-planning profession had any business mucking around with emotion.”

Compared with the country’s 85,000 CFPs, the Financial Therapy Association’s 300-plus members, including 32 outside the U.S., form a small, but rapidly growing, group of practitioners.

There is still some debate about the best way to bridge therapy and financial planning. Financial therapists now come from one of two “home disciplines” — either the financial-planning field or mental-health counseling. But a certified financial planner who offers financial therapy is not equipped to treat people coping with serious mental-health problems, and a psychotherapist shouldn’t give investment advice, said Alex Melkumian, a Los Angeles–based licensed marriage and family therapist who offers financial therapy.

“For your money, you want a fiduciary,” he said. “For your emotional health, you want a licensed psychologist or therapist who knows how to treat the diagnoses you have and respects confidentiality.”

Therapists should not be handing out financial-planning advice or telling clients what investments to buy, he said. Clients can idealize their therapists and try to please them. “Imagine if I’m saying you have to invest in this particular fund, or this is a strategy that will work for you 110%, and then it doesn’t work,” Melkumian said. “There would be resentment between them and me as the therapist, and it would cloud the treatment and make it ineffective.”

Some financial therapists post disclaimers explaining they can’t treat acute mental-health disorders; others say upfront that they won’t give investment advice. One possible solution to this conundrum is to have therapists and financial planners work side-by-side with the same clients, a strategy that Melkumian and Kahler, among others, advocate.

“When you start playing in the area of mental health, ethics and transparency and intention is so important,” Kahler said. “People are more vulnerable about money than anything else, so it absolutely screams for integrity from the providers.”

Under the Financial Therapy Association’s new certification program, certified financial therapists will be fiduciaries and must adhere to an ethical code that includes avoiding “controlling financial elements of the client’s life that may interfere with doing what is in the client’s best interest.” They won’t be allowed to sell financial products.

Does financial therapy work?

The field is so new that there hasn’t been a lot of research on its effectiveness. One 2018 study by professors at Kansas State University found that 13 couples who were taught a “love and money” curriculum — techniques similar to what they might encounter in financial therapy — felt happier and less stressed about money afterward, and reported significant reductions in money-related stress when they were interviewed three months later.

But true-believer clients like Sheri Reid Grant don’t need research to convince them of the benefits.

“The financial issues I struggle with are universal,” Grant said. “The only difference is a few zeros at the end of my net worth.”

She said therapy can be emotionally taxing, but she sticks with it in part because of her children: “I feel a huge responsibility to break the chains of family dysfunction around money instead of passing them on to my kids.”