The FCC has given its stamp of approval to T-Mobile and Sprint’s proposed merger, saying the deal will “enhance competition” and hasten 5G deployment. Those opposed say the merger defies common sense, creating a triumvirate of mobile giants that will “divide up the market, increase prices, and compete only for the most lucrative customers.”

The two mobile companies have been attempting to merge for years, ostensibly in order to compete with the considerably larger AT&T and Verizon. (Disclosure: TechCrunch is owned by Verizon Media, but this does not affect our coverage in the slightest.)

Previous attempts at deals were blocked more or less on the grounds that while a consolidated market might make the new T-Mobile/Sprint entity more competitive, it would be a net negative for consumers, who would have less choice than ever. The announcement of a $60 million FTC settlement over anti-consumer business practices by AT&T when they had the leverage to carry them out is a timely reminder of the general temperament of mobile carriers.

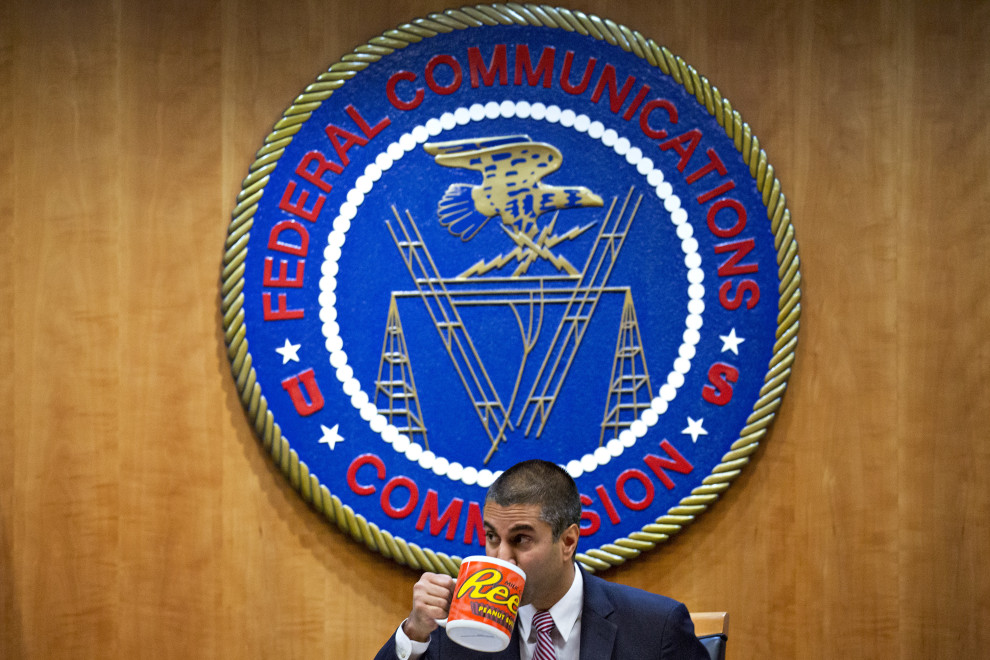

This latest attempt by the two companies (and backers like SoftBank, which stands to make a bundle on the deal) has met with more success, and the Department of Justice approved it in July. The DoJ’s proposed remedies for competition problems created by the merger apparently gave the FCC “further confidence” in its approval, which Chairman Ajit Pai signaled earlier this year — interestingly, before those remedies were proposed.

Among other things, Sprint must sell its Boost Mobile brand, and T-Mobile must sell its interest in Dish Network. The hope is that Dish, Boost and a few other players will somehow band together to form a new insurgent wireless network that will rise to compete with its former masters.

Sound a bit far-fetched? FCC Commissioner Rosenworcel thinks so as well.

“Instead of promoting vigorous competition among providers, today’s order justifies increased concentration by jerry-rigging a new provider dependent on the government dictating who sells what to whom and when,” she said in a statement.”

Commissioner Starks indicated his dissent on other grounds as well, specifically recent charges that Sprint has been irresponsibly deploying funds from the Commission’s Lifeline program for low-income mobile subscribers.

“Sprint may be responsible for the most egregious violations of our Lifeline rules in FCC history,” Starks wrote in a statement. “Our review should have been held in abeyance following the Chairman’s recent announcement of an investigation into Sprint’s alleged misappropriation of Lifeline support for 885,000 ineligible accounts. If substantiated, this would represent the misuse of nearly 10 percent of the funds for the entire program.”

More than anything else, though, critics remain skeptical of the basic idea that consolidation will produce increased competition. In fact, the Justice Department even thinks that may happen, which is why it is requiring the carriers to hastily assemble a new competitor out of whatever parts are left laying around, including some still being used by T-Mobile and others.

“The proposed transaction is exactly the type of merger that the Justice Department and the Commission have discouraged and rejected in the past: one that would harm competition and result in higher prices and poorer service, particularly for the most vulnerable consumers,” wrote Starks.

Others are concerned that the deal seemed to be a done deal even before Justice handed down its recommendations to improve competition following the merger.

“The FCC majority prejudged the merits of this merger two months before the Justice Department found the combination of T-Mobile and Sprint to be anticompetitive and required the creation of a new fourth competitor to pass legal muster. Despite this radical change in the merger, Chairman Pai has refused to put the new arrangement out for public comment,” noted Gigi Sohn, who was counselor to former FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler.

“Three of my colleagues agreed to this transaction months ago without having any legal, engineering, or economic analysis from the agency before us,” wrote Rosenworcel. “The procedural irregularities that have plagued the FCC’s review of this transaction make it difficult to ensure this agency’s findings are credible—especially when in so many key respects they are at odds with the findings of the Department of Justice.”

Proponents of the deal lean heavily on promises being made that “New T-Mobile,” as it is referred to in the decision, will use its new position to quickly and efficiently deploy 5G to many markets it might not otherwise have reached.

“This transaction will provide New T-Mobile with the scale and spectrum resources necessary to deploy a robust 5G network across the United States,” said Chairman Pai in his statement regarding the decision. “New T-Mobile will make the mobile broadband market more competitive in large swaths of rural America where neither Sprint nor T-Mobile is currently a strong competitor to AT&T and Verizon.”

Pai says the idea that reducing the number of major carriers from four to three will be harmful to competition is a “simplistic, backward-looking claim.” The truth, he says, is that in many places this merger will increase the number of competitors from two (Verizon and AT&T) to three as T-Mobile enters the market. That’s fair speculation to be sure, but as Commissioner Starks points out, that idea too is simplistic. The truth is that reducing the number of major carriers will likely have serious and immediate negative effects as well as well as Pai’s imagined long-term benefits.

“In the short term, this merger will result in the loss of potentially thousands of jobs. In the long term, it will establish a market of three giant wireless carriers with every incentive to divide up the market, increase prices, and compete only for the most lucrative customers,” Starks writes.