For one Iowa woman, the most frustrating and scary time of her life started when her debit card was declined.

In the days leading up to St. Patrick’s day, health care worker Adunni Noibi felt sick. Yet when the mother of three stopped at her local pharmacy for medication, her debit card wouldn’t work. When she checked her account balance on her app, there was money in her account, so Noibi figured it was just a glitch.

But it wasn’t just her card malfunctioning. Unbeknownst to Noibi, a debt collector had filed a lawsuit in December seeking about $3,300 on student loans she took out in 1998. The debt collection company had obtained a judgement and frozen not only all her bank accounts, but her childrens’ accounts where she was listed as a co-signer.

Days after the incident at the drugstore, Noibi felt well enough to get out of bed, only to realize her mortgage had not been paid. When she called the bank, she finally learned her accounts were frozen. This was a much bigger deal than simply requesting a new debit card, she realized.

“I was in tears, bawling,” Noibi says. “These are crazy times right now, you see everyone at the store stocking up on toilet paper and supplies and I had nothing, no groceries, nothing.”

Debt collection lawsuits are on the rise

Noibi is not the only one who’s been hit with a debt collection lawsuit that’s turned life upside down.

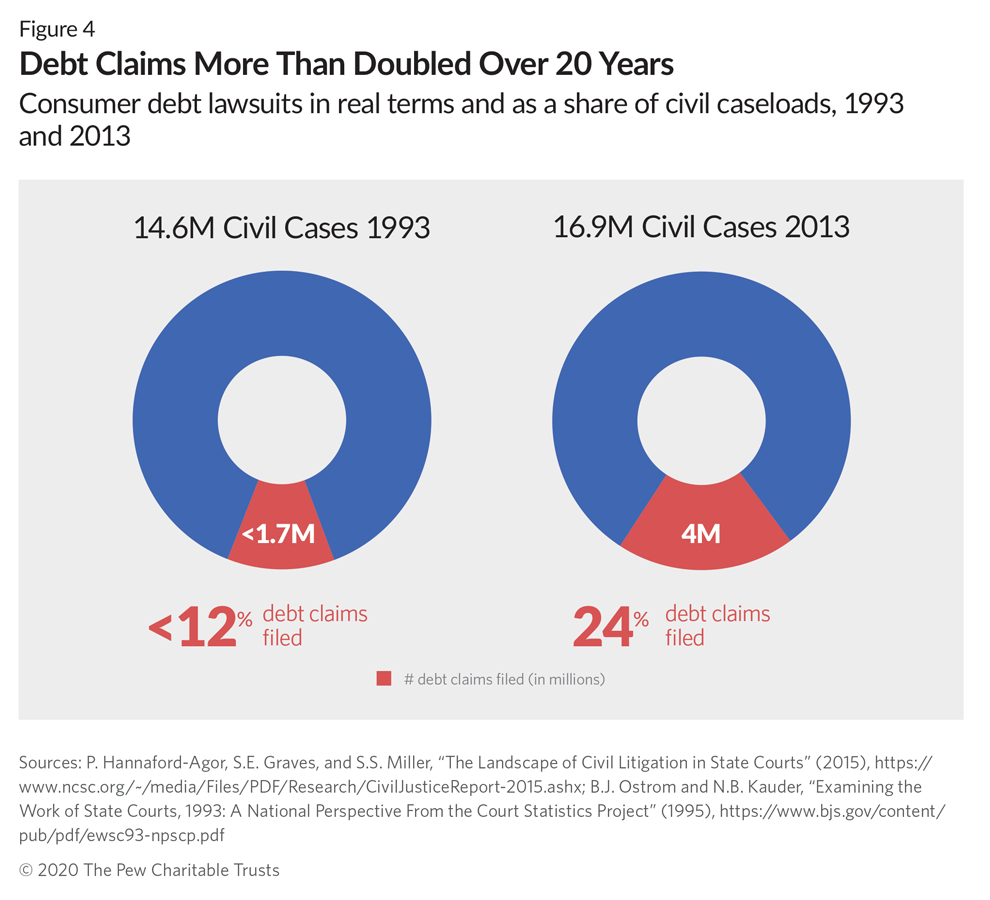

The number of debt collection cases has risen significantly, according to a new report from Pew Charitable Trusts. Debt lawsuits made up about 1 in 9 civil cases in all state courts in 1993. By 2013, they accounted for 1 in 4 lawsuits and available state data since 2013 suggests that this trend has continued, Pew found.

Like Noibi, many times consumers fail to respond at first to these lawsuits, either because they’re unaware that the case is underway or because they don’t have the resources to fight it. About 15% of Americans said they had been sued by a debt collector, according to a 2017 report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Of those, only about 26% attended their court hearing. In debt collection lawsuits that Pew reviewed, more than 70% resulted in default judgments for the collectors — a sign that many people do not respond when sued.

That’s because many times, the average amount owed is less than $5,000 and the cost for consumers to hire a lawyer and pay court fees is usually more than that, says Erika Rickard, director of the civil legal system modernization project at Pew. Less than 10% of consumers had a lawyer represent them in debt collection lawsuits filed between 2010 and 2019.

Yet those who do respond and hire a lawyer are more likely to win their case or reach a mutually agreed settlement to resolve their outstanding debts. Of the 300,000 debt cases brought in Virginia between April 2015 and May 2016, lawsuits were more likely to be dismissed if consumers had legal representation, according to a report by the National Center for State Courts. Pew noted a similar study focusing on Utah courts found that from 2015 to 2017, 53% of consumers won debt collection lawsuits against them when they had a lawyer, compared to the 19% that did not.

Because so few consumers attend hearings, debt collectors tend to bank on getting a default judgment, giving them the ability to garnish wages, place liens on property and freeze bank accounts. For those who have had a default judgement issued against them, they’ll need to either work with the debt collection company to settle or go to court to and ask a judge to have the default judgement set aside.

How Noibi sought help

Noibi is one of the few consumers who, once aware of the situation, chose to fight back. After weeks of trying to get things resolved with the debt collection company, Noibi was at her wit’s end.

At that point, her brother suggested hiring a lawyer. “How can I get a lawyer when I have no money?” Noibi recalls asking. The last thing she wanted to do was take on an additional bill. “I was barely getting by, let alone to have to pay a lawyer to have to do something.”

But time was running out. Despite getting temporary financial help from her mom, Noibi had bills to pay and three children to take care of.She was also worried that the funds from her tax returns and stimulus check, both of which were set to hit her account in April, would also be frozen — or worse, simply taken.

She sought out Iowa Legal Aid. Thankfully, staff lawyer Jayme Wiebold not only agreed to take the case, but had experience with this particular debt collection agency and its tactics. Noibi never received any notifications about the pending lawsuit or the actions taken against her, she says. It was only after she called the bank that she even received an official letter notifying her of the frozen accounts.

“If I’d received something that said someone was going to be taking my money, I would’ve been on the phone immediately trying to figure something out,” Noibi says.

With help from Iowa Legal Aid, Noibi was able to successfully stop the debt collection company from keeping the account frozen and taking her money. The debt collection company dropped the suit after Noibi agreed to not sue the agency for its collection practices.

For those that find themselves in a similar situation, there are a number of national and state organizations that provide free or low cost legal assistance.

Americans could face even more of these cases

The number of Americans dealing with debt collection lawsuits could grow as the economic downturn continues. “We know that debt collection was up significantly even when the economy was booming,” Rickard tells CNBC Make It. Roughly one in three Americans with a credit history have had a debt in collections, according to the Urban Institute.

“As we see job losses and an economic downturn due to the pandemic, we could very well see household debt continue to fall into collection, and ultimately find its way into the courts,” Rickard says.

Noibi emerged from the experience relatively unscathed with a few unpaid bills and several weeks of anxiety. But some Americans with judgments entered against them end up with losing wages and sometimes even need to declare bankruptcy to avoid additional payments.

Yet the experience has shattered Noibi’s trust in banks, at least for now. After her accounts were unfrozen, Noibi took all the money out of her bank accounts. “I know that sounds crazy, but if this company can do it, what stops someone else from coming to do this?” Noibi says.

“If I need to pay something now, I put money into the bank to pay it, which is sad, but it’s the reality.” she adds. “I’m taking one day at a time right now.”