Wagering on the stock market bounce was always a long shot. Now it looks like a sucker’s bet.

While the reemergence of hotter-than-forecast inflation was the proximate cause of the latest plunge, another force is also at play in the second-longest series of weekly declines since May: high valuations. One lens that takes account of the increasingly anemic growth expected in S&P 500 earnings shows equities as richly priced as they’ve been in almost three decades of data.

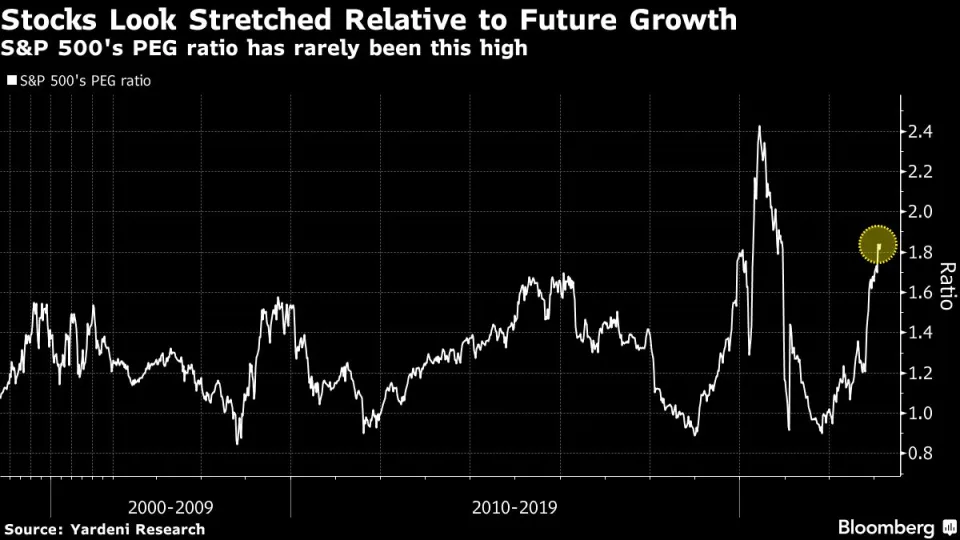

The model, a tool of Fidelity Investments legend Peter Lynch a generation ago, is the PEG ratio, the market’s price-earnings multiple divided by its forecast growth rate. The higher it is, the more expensive shares are — and right now, at about 1.8 based on longer-term estimates, the indicator’s message strikes many as ominous.

Stretched multiples at a time of stiffening Federal Reserve resolve to whip inflation now is a cocktail investors have wanted no part of in February. Over a holiday-shortened week that concluded with an unexpected acceleration in the central bank’s preferred inflation gauge, the S&P 500 slid 2.7%, extending a downdraft that risks erasing all of 2023 gains.

“Valuations do seem stretched on most earnings multiples, but when you insert the level of growth and the fact that growth is slowing, they look even more stretched,” Peter van Dooijeweert, head of multi-asset solutions at Man Solutions, said by phone. “Either the Fed needs to pivot and rates have to come down, or when the Fed pivots, earnings will resume a very strong growth trajectory. Those are pretty big things to wish for.”

Since peaking earlier this month, the S&P 500 has erased more than half of a year-to-date gain that at one point reached almost 10%. The Dow Jones Industrial Average has already wiped out its 2023 advance after falling four weeks in a row.

The retreat is a moment of reckoning for bulls who have defied falling profits and rising rates to bid up shares. At 18 times profits, the S&P 500 is trading just slightly above its 10-year average. Yet when stacked next to a wave of profit downgrades, the picture is less reassuring.

Amid mounting concern over an economic recession, Wall Street analysts are cutting profit forecasts. The expected rate of income growth for 2023 has turned negative, down from a positive projection of almost 10% in June, data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence show.

It’s not just for this year that earnings sentiment is souring. Forecast profits for the next three to five years have seen a broad reduction, with the pace of expansion shaved by half since the start of 2022, according to data compiled by Yardeni Research.

At the center of the downgrades is concern that the post-pandemic boom, driven by unprecedented government stimulus and a swift shift to online spending, is unsustainable.

The worsening growth outlook has led to a relentless surge in the PEG ratio. As it stands now, based on long-term profit forecasts, the S&P 500 is roughly 20% more expensive than it ever was during the internet bubble.

“The current nosebleed level of valuations seen in the US PEG ratio is a result of the ‘growth’ long-term EPS rug being pulled out from under investors,” Albert Edwards, the notoriously glum global strategist at Societe Generale, wrote in a note this week. “This all means that the current PE of around 18x is very vulnerable, and not just against sharply higher cash/bond yields (TINA is dead and buried),” he said, referring to the abbreviation for “there is no alternative” to buying stocks.

Like many valuation models, the PEG isn’t a great timing tool. Its prior high, made in mid-2020, saw stocks continue to march upward for more than a year. The ratio also peaked in 2009 and 2016, neither of which proved an immediate death knell for bulls.

Theoretically, stretched valuations are no hurdle for equities as long as corporate profits are able to catch up. Whether that will happen again this time is the biggest question facing equity investors today.

In the eyes of Ed Yardeni, the founder of his namesake firm, the PEG ratio reflects two warring narratives — one showing investors are willing to look past any short-term roadblocks and pay up for stocks, and another reflecting mounting skepticism over growth.

“It’s signaling caution because you got a tug of war between the relative pessimism of analysts and the relative optimism of investors,” Yardeni said. “It may just turn out that it’s a tug of war where neither side makes any progress, which is what it could be for a little while.”

Since June, the S&P 500 has been mostly stuck in an 800-point band, creating headaches for bulls and bears alike. Over the stretch, the index’s closing prices averaged at 3,939 — about 30 points away from where it ended Friday.

With the benchmark gauge surging as much as 17% from its October low, some market watchers have viewed the rebound as the start of a new bull market. To David Donabedian, chief investment officer of CIBC Private Wealth US, it’s too early to call the all-clear given stocks have yet to start looking like bargains.

“It didn’t say that back in October either when we had the beginning of this market rally,” Donabedian said. “So to me, we have not seen that capitulation phase that every bear market has where investors throw in the towel, give up hope and you get a market that looks objectively inexpensive. We’re not there yet.”