The Arctic permafrost really should stay frozen. In many places it’s been frozen for tens of thousands of years, locking away greenhouse gasses and ancient diseases.

Unfortunately, our planet’s changing climate is denting permafrosts around the world. And now NASA-funded research has confirmed that the expected gradual thawing of the Arctic permafrost is being dramatically sped up by a natural phenomenon known as thermokarst lakes.

These lakes form when a lot of ice in the deep soil melts. Water takes up less space than ice, so this leaves room for water to collect from other sources as well, including rain and snow.

“When the [thermokarst] lakes form, they flash-thaw these permafrost areas,” explained ecologist Katey Walter Anthony from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

“Instead of centimetres of thaw, which is common for terrestrial environments, we’ve seen 15 metres of thaw beneath newly formed lakes in Goldstream Valley within the past 60 years.”

Permafrost covers about 24 percent of the exposed land in the Northern Hemisphere. There’s a lot of it. In some areas of the Arctic, the frozen ground is up to 80 metres (260 feet deep).

But despite its name, permafrost is not always permanent. With unusually warm weather, especially further away from the Arctic, it can melt, even on a semi-regular basis; however, deep in the Arctic a lot of it has stayed unmelted for tens of thousands of years – until now.

And that’s where the problems start. The Arctic landscape also holds one of the largest natural reservoirs of organic carbon in the world. It’s all locked up in the ice, not causing any trouble at the moment.

But when it slowly melts, the soil microbes eat the carbon and produce carbon dioxide and methane, which enters the atmosphere and contributes to global warming.

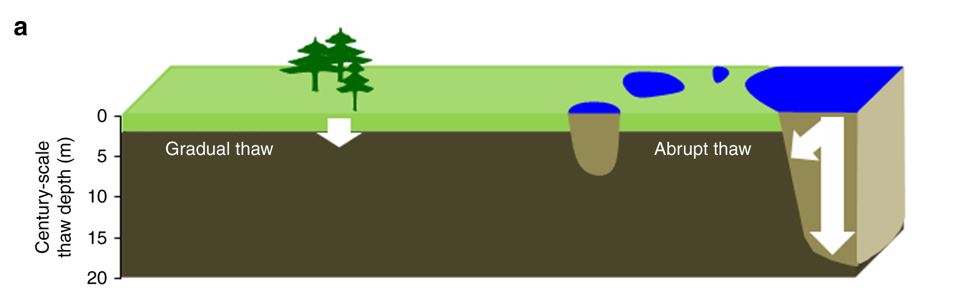

Thermokarst lakes take this process to a whole new level, with permafrost thawing deeper and more quickly – which the researchers call abrupt thawing.

“Within decades you can get very deep thaw-holes, metres to tens of metres of vertical thaw,” says Walter Anthony.

“And we have very easily measured ancient greenhouse gases coming out.”

Just last year tell-tale signs of bubbling lakes sprung up in over 200 locations in Siberia. But this abrupt thawing might be worse than we originally thought, according to researchers from the US and Germany.

The team, part of NASA’s Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE), travelled to Alaska and Siberia, and measured the methane bubbling out of 72 locations in 11 thermokarst lakes.

They then compared the emissions to five locations where gradual thawing occurs instead.

“Abrupt thaw accelerates mobilisation of deeply frozen, ancient carbon, increasing carbon-14 depleted permafrost soil carbon emissions by approximately 125-190 percent compared to gradual thaw alone,” the researchers explain in the paper.

Adding computer modelling and satellite imagery from 1999 to 2014, they were able to estimate the amount of permafrost converted to thawed soil – and it’s bad news there, too.

“Over a few decades, thermokarst lake growth releases substantially more carbon than lake loss can lock in permafrost again [when the lake bottoms refreeze],” explains co-author Guido Grosse, from the Alfred Wegener Institute.

Although thermokarst lakes are currently not included in global climate change models because they’re small and scattered, the team says this new research shows how important it is to include them.

Human fossil fuel emissions are still the number one source of greenhouse gas emissions, but these lakes are important to keep an eye on.

“We don’t have to wait 200 or 300 years to get these large releases of permafrost carbon. Within my lifetime, my children’s lifetime, it should be ramping up … Within a few decades, it should peak,” Walter Anthony added.

“You can’t stop the release of carbon from these lakes once they form.”

The research has been published in Nature Communications.