There’s a hole in the Martian atmosphere that opens once every two years, venting the planet’s limited water supply into space — and dumping the rest of the water at the planet’s poles.

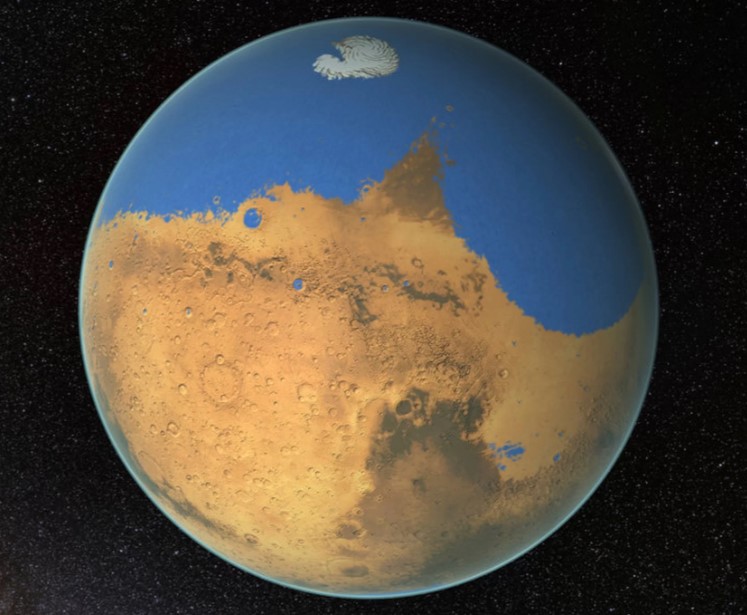

That’s the explanation advanced by a team of Russian and German scientists who studied the odd behavior of water on the Red Planet. Earthbound scientists can see that there’s water vapor high in the Martian atmosphere, and that water is migrating to the planet’s poles. But until now, there was no good explanation for how the Martian water cycle works, or why the once-drenched planet is now a dry husk.

The presence of water vapor high above Mars is puzzling because the Red Planet has a middle layer of its atmosphere that seems like it should be shutting down the water cycle altogether.

“The Martian middle atmosphere is too cold to sustain water vapor,” the researchers wrote in the study, which was published April 16 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

So how is water crossing that middle-layer barrier?

The answer, according to computer simulations in the current study, has to do with two atmospheric processes unique to the Red Planet.

On Earth, summer in the Northern Hemisphere and summer in the Southern Hemispheres are pretty similar. But that’s not the case on Mars: Because the planet’s orbit is much more eccentric than Earth’s, it’s significantly closer to the sun during its southern hemisphere summer (which happens once every two Earth years). So summers on that part of the planet are much warmer than summers in the Northern Hemisphere.

When that happens, according to the researchers’ simulations, a window opens in Mars’ middle atmosphere between 37 and 56 miles (60 and 90 kilometers) in altitude, allowing water vapor to pass through and escape into the upper atmosphere. At other times, the lack of sunlight shuts down Martian water cycles almost entirely.

Mars is also different from Earth in that the Red Planet gets frequently overtaken by giant dust storms. Those storms cool the planet’s surface by blocking light. But the light that doesn’t reach Mars’ surface instead gets stuck in the atmosphere, warming it and creating conditions better suited to moving water around, the scientists’ simulations showed. Under global dust-storm conditions, like the one that enveloped Mars in 2017, tiny particles of water ice form around the dust particles. Those lightweight ice particles float into the upper atmosphere more easily than other forms of water, so during those periods more water move into the upper atmosphere.

Dust storms can move even more water into the upper atmosphere than the southern summers, the researchers showed.

Once the water passes through the middle boundary, the researchers wrote, two things happen: Some of the water drifts north and south, toward the poles, where it’s eventually deposited. But ultraviolet light in the upper atmosphere can also sever the bonds between the oxygen and hydrogen in the molecules, causing the hydrogen to escape into space, leaving the oxygen behind.

This process could be part of the story of how a once-drenched Mars has ended up so dry in its current epoch, the researchers wrote.