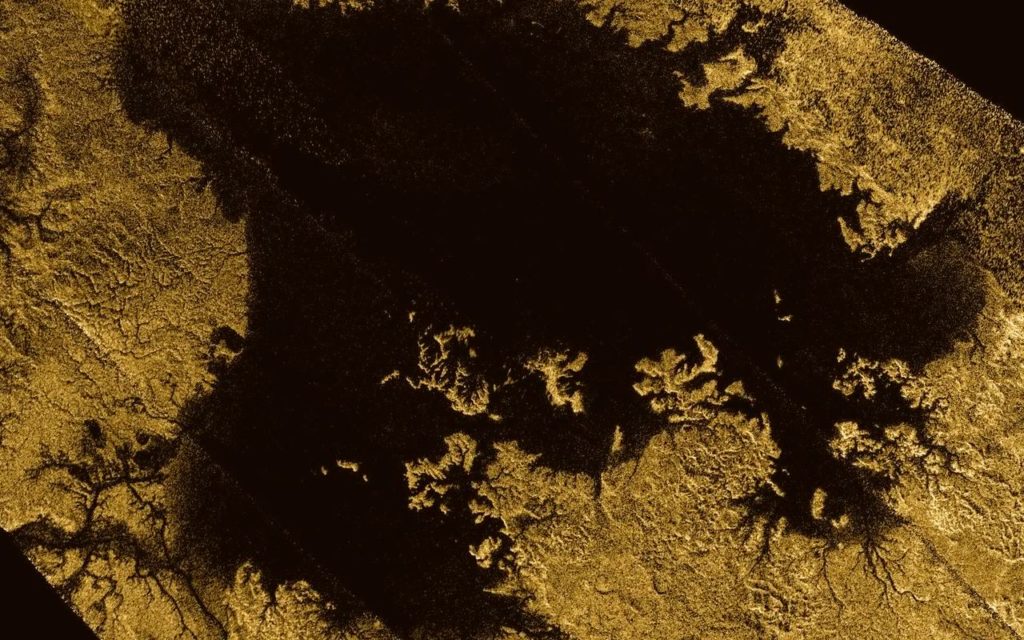

Researchers using data from NASA’s Cassini mission have discovered a striking similarity between Earth and Saturn’s moon Titan. Just as the surface of Earth’s oceans lies at an average elevation referred to as “sea level”, Titan’s seas also lie at an average elevation. Titan is the only world in our solar system other than Earth known to have stable liquid on its surface. Instead of water, Titan’s lakes and seas are filled with hydrocarbons, mostly methane and ethane. Water ice, covered by a layer of solid organic material, forms the bedrock surrounding these lakes and seas.

The new study, which was published in the journal Geophysical Research letters, found that Titan’s seas follow a constant elevation relative to Titan’s pull. Titan’s smaller lakes are found at elevations several hundred feet, or meters above the moon’s sea level. On Earth, lakes are commonly found at high elevations. Lake Titicaca, is more than 12,000 feet (3,700 meters) above sea level.

“We’re measuring the elevation of a liquid surface on another body 10 astronomical units away from the Sun to an accuracy of roughly 40 centimeters. Because we have such amazing accuracy we were able to see that between these two seas the elevation varied smoothly about 11 meters, relative to the center of mass of Titan, consistent with the expected change in the gravitational potential. We are measuring Titan’s geoid. This is the shape that the surface would take under the influence of gravity and rotation alone, which is the same shape that dominates Earth’s oceans,” said Alex Hayes, assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York via a release.

Another finding presented in the new study is that Titan’s liquid bodies seem to be connected under the surface by means similar to an aquifer system on Earth. Hydrocarbons appear to be moving underneath the surface of Titan in a manner similar to the way water flows through porous rock or gravel on Earth. This is similar to the manner that neighboring lakes ‘communicate’ with each other and maintain a common liquid level.

The study used data collected by Cassini’s radar instrument until just a few months before the spacecraft was directed to burn up in Saturn’s atmosphere last fall. The researchers also made use of a new topographical map of Titan which was published in the same issue of Geophysical Research letters as the study.

It took about a year to create the map, according to Cornell doctoral student Paul Corlies, lead author on “Titan’s Topography and Shape at the End of the Cassini mission.” The map combines all available Titan topography from multiple sources.

The map also revealed new mountains, none higher than approximately 2,297 feet (700 meters) and other new features on the smoggy moon. This new tool helped to reveal that Titan is a bit flatter, more oblate, than previously thought, indicating that there is more variability in the thickness of Titan’s crust than was previously thought.

“The main point of the work was to create a map for use by the scientific community,” said Corlies, who began to receive inquires about how to use the map within 30 minutes of the data set becoming available online.