Pension systems around the world require or encourage the provision of financial support to retired individuals from a range of sources. Yet, every system provides higher retirement income to men than women.

This is because the origins of most pension systems have been developed on the basis of a “normal life course,” which inevitably defines a standard. This often implies continuous full-time employment for decades.

But, such assumptions do not represent reality for many individuals in the workforce, male or female. Flexible, non-standard work patterns are increasing around the world with increasing mobility and greater digitization, which has been accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the consequences of this standard approach is that the level of poverty among retirees is 50% higher for women than men, according to the OECD.

A Global Comparison

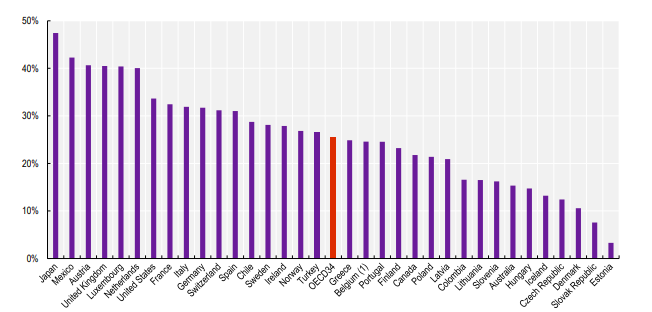

A gender pension gap exists in every retirement income system. It is the difference between the average male pension and the average female pension, expressed as a percentage of the average male pension. That is, the calculation is based on those who are currently receiving a pension. Hence, if there is no difference in the current pensions, the gap is zero, whereas if the average male pension is double the average female pension, the gap is 50%.

Figure 1 shows the gender pension gap for most OECD countries. The range is very broad, with Japan having a gap of almost 50%, whereas Estonia’s gap is less than 5%.

Figure 1: Gender Gap in Pensions in Selected OECD Countries

What Causes the Gender Pension Gap?

The many causes of the gender pension gap can be broadly grouped into issues related to: employment, pension design and sociocultural issues.

Employment issues: There is a direct relationship between employment patterns and the resulting pensions in most systems. On average, women’s pensions are lower for a few reasons. For example, women may have shorter careers due to, on average, a slightly later start in the labor force and earlier retirement, which often relates to having an older partner.

Women are also more likely to work part-time, which might be a choice, but is often present to cover the requirements of the role as a caregiver. Reduced employment for a number of years has long-term effects on the promotion opportunities and hence lifetime earnings for some women.

This lack of job progression has a compounding effect on pay and the subsequent pension. Indeed, the gender wage gap in the OECD for full-time workers was 13% in 2018. This outcome is partly due to a lower average wage in female-dominated industries than in male-dominated industries.

And finally, there are instances where women get paid less than men for doing the same job.

Given these historic and current differences in employment, it is not surprising that, on average, male pensions from employment-based pension arrangements, whether paid from social insurance or occupational-based pension schemes, are higher than female pensions.

Pension design issues: Although the major causes of the gender pension gap are employment-related, there are also several design features in pension systems that aggravate the issue. For example, eligibility restrictions in some arrangements require a minimum income or a minimum number of hours to be worked. Periods of paid parental leave may not necessitate contributions or the accrual of pension benefits. And most systems don’t provide pension credit for time spent caring for young children — however, there are examples where credits occur in this context.

Additionally, there’s an absence of survivor’s pension benefits, which affects more women than men due to their longer life expectancy. For the same reason, the lack of indexation of pensions during retirement, wherein pension amounts increase to account for inflation, more greatly impacts women.

A global trend in the provision of pensions is the gradual replacement of defined benefit (DB) schemes with defined contribution (DC) arrangements. Under DB pension schemes, the same pension is paid for men and women, given the same salary and service. Yet this outcome does not occur with the DC plans in many systems as gender-based annuity rates lead to lower pensions for women than men, for the same accumulated balance.

Sociocultural issues: In addition to employment-related and pension-design issues that generate the gender pension gap, there are several features or characteristics within many societies and cultures that restrict the opportunity to reduce the gap.

Variations in working patterns in some societies reflect cultural differences or preferences. For example, gender stereotyping can lead to educational differences and an expectation that women do more unpaid family work.

When child care is needed, but there’s an absence of affordable and appropriate-quality child care, the work opportunities for parents are restricted. Further, child care costs can negatively impact voluntary pension contributions, as these costs are sometimes paid directly by women.

Lower financial literacy among women may also affect their financial decisions. Communication and campaigns from pension funds often ignore needs that are specific to women or use language that does not appeal to women. Within defined contribution arrangements, where investment choice is available to individuals, women are often more risk-averse, which can lead to lower returns.

And, in the context of divorce, pension rights accrued during a partnership are not normally split evenly, which can lead to many women having lower pension benefits.

In summary, the causes of the gender pension gap are mixed and varied. No two countries are the same. Yet, in every pension system, there is a range of employment-related, pension design and sociocultural issues that lead to a significant difference between the average level of retirement income received by men and women.

In addition to the above causes, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the retirement savings of women to a greater extent than men due to its significant impact on part-time and casual workers, as well as its effect on some female-dominated industries, such as hospitality and tourism.

Given the variety of causes, there is not a single solution. Rather, the issue needs to be tackled from several perspectives, including employment differences, pension design and cultural issues.

Recommendations to Reduce the Gender Pension Gap

In light of the many causes of the gap around the world, the following actions should be taken to improve pension outcomes for women around the world.

Actions by employers: Employers can encourage flexibility in terms of where and when employees work; remove the range of distinctions that exist between part-time and full-time employees; and ensure that parental leave may be taken by either parent.

Actions within the pension industry: The pension industry itself could remove all eligibility restrictions for individuals to join employment-related pension arrangements; introduce pension credits for carers, so that those who are caring for young children or aging relatives are not penalized in their retirement years; remove gender-based annuity rates; require all pensions to have some form of indexation; and introduce publicly available models and calculators to show the impact of different working arrangements and career gaps on retirement pensions.

Actions by governments: Governments can provide affordable quality child care; provide greater flexibility for pension contributions, recognizing that employment patterns over a working career can vary considerably; require that pension contributions continue during periods of paid parental leave and carer leave; permit pension contributions into the pension account of a spouse or partner; ensure that pension rights accrued during a partnership are taken into account in divorce proceedings; and ensure that there is no difference in the retirement ages for men and women.

Most of these changes can occur within government-financed social insurance arrangements, as well as in the second pillar private pension arrangements, with appropriate legislation and government support.

Now is the time to act to reduce the gender pension gap in the future.