The animal kingdom is likely older than current scientific understanding suggests, according to a study published in the journal Palaeontology.

Researchers found that a marine creature, known as Stromatoveris psygmoglena, provides a crucial link between the lifeforms of the Ediacaran Period (635 to 541 million years ago) and those of the later Cambrian (541 million to 485 million years ago). The transition between these two eras is key to understanding the origin of animals.

Fossil evidence shows that during the Ediacaran Period, a wonderful variety of complex multicellular lifeforms began to emerge. But determining how these organisms—many of which resemble tubes or fronds—should be classified has proved challenging for researchers.

“The Ediacaran biota includes fossils of some of the oldest large and complex lifeforms known,” Jennifer Hoyal Cuthill, a paleobiologist from the University of Cambridge and the Tokyo Institute of Technology, told Newsweek.

“These early fossils are not quite like anything alive today. So there has been considerable scientific debate on where they belong in the tree of life,” she said. “While it had been suggested that at least some of the large, complex fossils might have been early animals, almost every other possibility has also had its advocates: from seaweeds to giant protozoans.”

It is unclear how Ediacaran macroorganisms—those that can be seen with the unaided eye—relate to modern animals because they appear to have almost entirely died out with the Cambrian explosion, a rapid increase in biodiversity that took place between roughly 540 and 520 million years ago. Most of the major animal groups that we know today first appeared in the fossil record during this period.

But now, Cuthill and her colleague Jian Han, from Northwest University, China, have found evidence that some Ediacaran organisms were, in fact, animals.

For their study, the researchers examined more than 200 recently discovered and exceptionally well-preserved fossils of S. psygmoglena, which were found in Chengjiang County, China, and have been dated to around 518 million years ago. Some paleobiologists had previously concluded that S. psygmoglena was a type of animal.

Cuthill and Han then used computer analysis to compare the evolutionary relationships between members of the Ediacaran biota—a term that refers to the organisms of the Ediacaran Period—and other organisms such as single-celled protozoans, algae, fungi and nine animal types that appeared after the Cambrian explosion, including Stromatoveris psygmoglena.

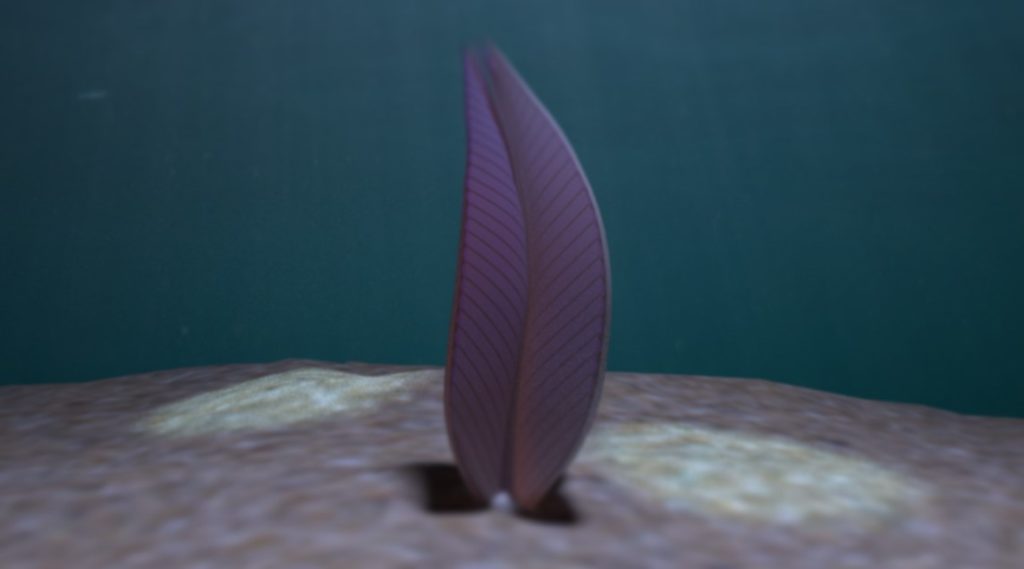

The analysis showed that Stromatoveris psygmoglena and seven key members of the Ediacaran biota formed a “distinct evolutionary group” of early animals, which has been named Petalonamae, that sits on its own branch of the tree of life. Members of this group share very similar anatomies, including multiple branched frond-like structures—the leaf or leaf-like part of palms, ferns, or similar plants.

Classifying these members of the Ediacaran biota and Stromatoveris psygmoglena in a single group means that the animal kingdom is older than we once thought, Cuthill explained.

“Our results have several implications for early animal evolution, suggesting that some earlier ideas need to be revised,” she said. “By including these members of the Ediacaran biota among the animals, we gain a new perspective on the origin of the animal kingdom, which must have originated before these fossils first appeared around 570 million years ago.”

“The link between Cambrian Stromatoveris and the Ediacaran biota also demonstrates that this group of early animals, called Petalonamae, survived much longer than many had thought and were not wiped out when the Cambrian explosion began,” she said.